Arctic sea ice is already disappearing rapidly but our research shows winter storms are now further accelerating sea ice loss.

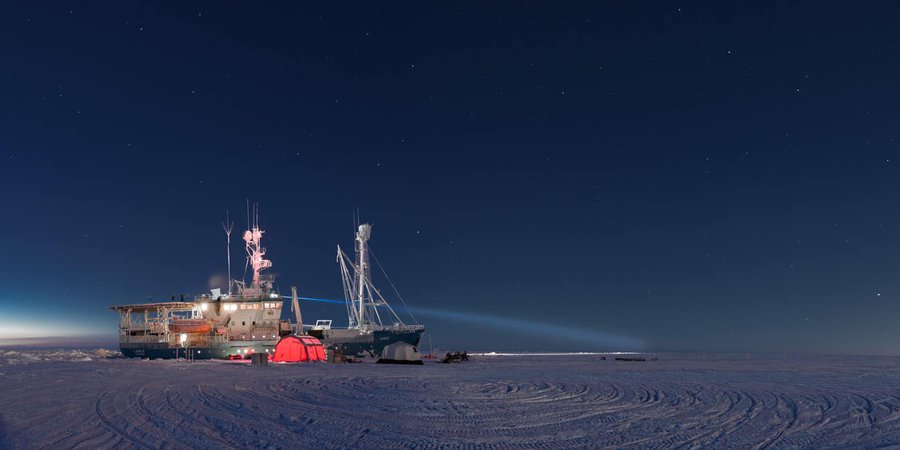

The research is based on data we gathered during an expedition on a small Norwegian research vessel, the Lance, that was left to drift in the Arctic sea ice for five months in 2015.

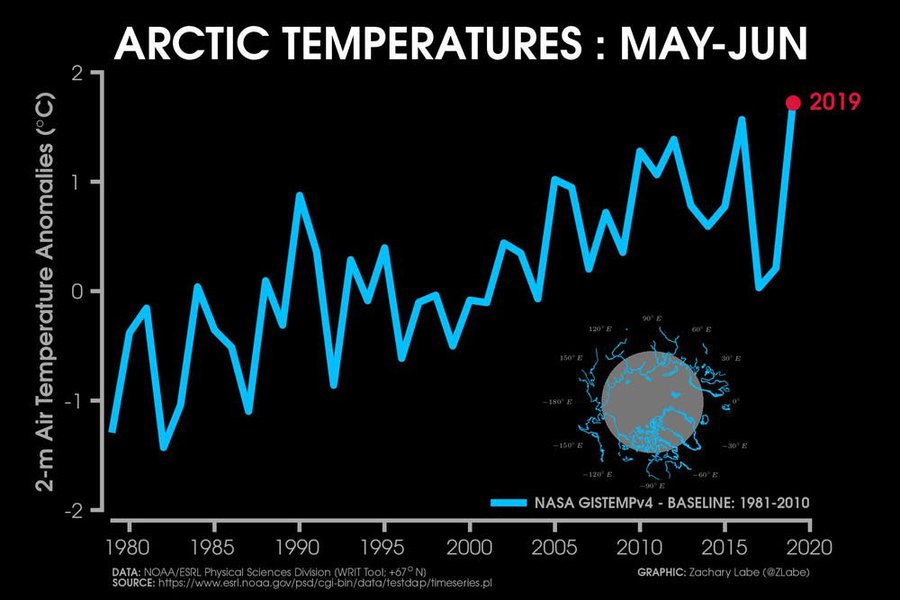

Time series of air temperature anomalies in the Arctic for the period 1981-2010: Temperatures in the Arctic in May and June 2019 period were the warmest in the satellite records. Zack Labe (@ZLabe)

The expedition was intense and felt more like going to the Moon than going on a typical research cruise. What took us by surprise were the many winter storms that battered the ice (and our ship and ice camp).

It has taken us years to collate these data but now we know the winter storms play a key role in the fate of Arctic sea ice, particularly in the Atlantic sector of the Arctic.

Norwegian research vessel ‘Lance’ frozen in the Arctic sea ice in February 2015 during the N-ICE2015 expedition. Paul Dodd (NPI)

How winter storms amplify climate change

On average, about 10 extreme storms will reach all the way to the North Pole each winter. While these winter storms are short (they last on average 6-48 hours), they can be incredibly intense.

During a storm in winter 2015 we saw the air temperature rise from -40℃ (-40℉) to 0℃ (32℉) in just a day, and then fall back to -30℃ (-22℉) the next day, when cold Arctic air returned after the storm.

These storms bring heat, moisture and strong winds into the Arctic, and next we look at how they impact sea ice and its surroundings.

Warming and weakening the ice

The heat from the storms warms up the air, snow and ice, slowing down the growth of the ice. Moisture from the storms falls as snow on the ice. After the storm, the blanket of snow insulates the ice from the cold air, further slowing the growth of the ice for the remainder of winter.

The strong winds during the storms push the ice around and break it into pieces, making it more fragile and deforming it, more like a boulder field.

The strong winds also stir the ocean below the ice, mixing up warmer water from deeper waters to the surface where it melts the ice from below. This melting of the ice in the middle of winter can happen for several days after the storms when the air is already back to well below freezing.

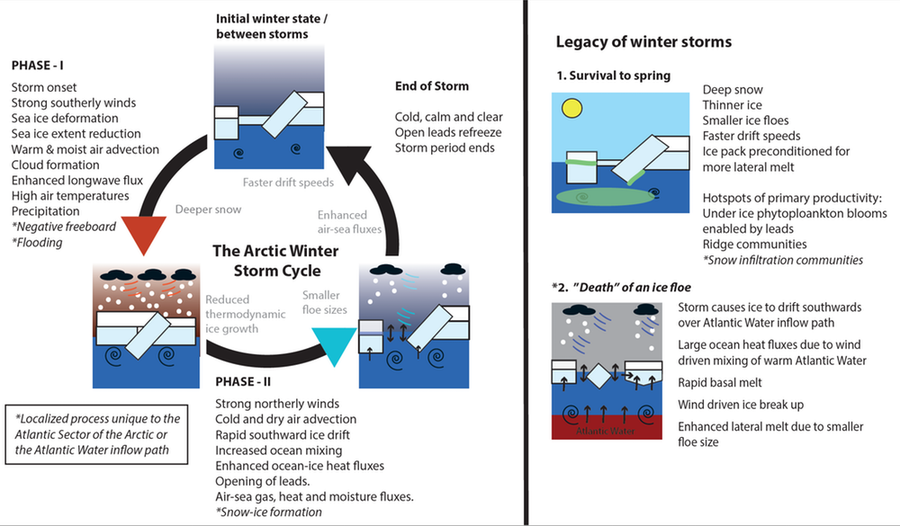

Processes related to Arctic winter storms. In the first storm phase, strong southerly winds compress the ice cover and transport warm air, moisture, and bring strong winds. In the second phase, northerly winds transport ice southwards. After the storm has passed, cold and calm conditions return, allowing new ice to grow in leads. When the next winter storm arrives, it further drives the ice cover into a relatively thin-ice, snow-covered mosaic of strongly deformed ice floes. These new conditions impact surrounding ecosystems by shaping habitats and light conditions. Graham et al., 2019 (Scientific Reports)

Thinner ice, shelter for life and accelerated melting

The breakup of the ice opens big passages of open water between ice floes, called leads. In winter these passages end up refreezing rapidly, generating new super-thin ice.

These thinner refrozen patches of ice let more light through in the following spring, allowing ocean plants (phytoplankton) to bloom earlier.

The rougher sea ice landscape becomes a shelter for many ice-associated Arctic organisms, including ice algae, becoming biological hot spots in the following spring.

The broken up and deformed ice drifts faster, reaching warmer waters where it melts sooner and faster.

So really, winter storms precondition the ice to a faster melt in the following spring with an impact that continues well into the following season.

Why is Arctic sea ice declining?

Winter sea ice cover in the Atlantic sector of the Arctic has been retreating at a record breaking pace, especially in the Barents Sea off Norway and Russia.

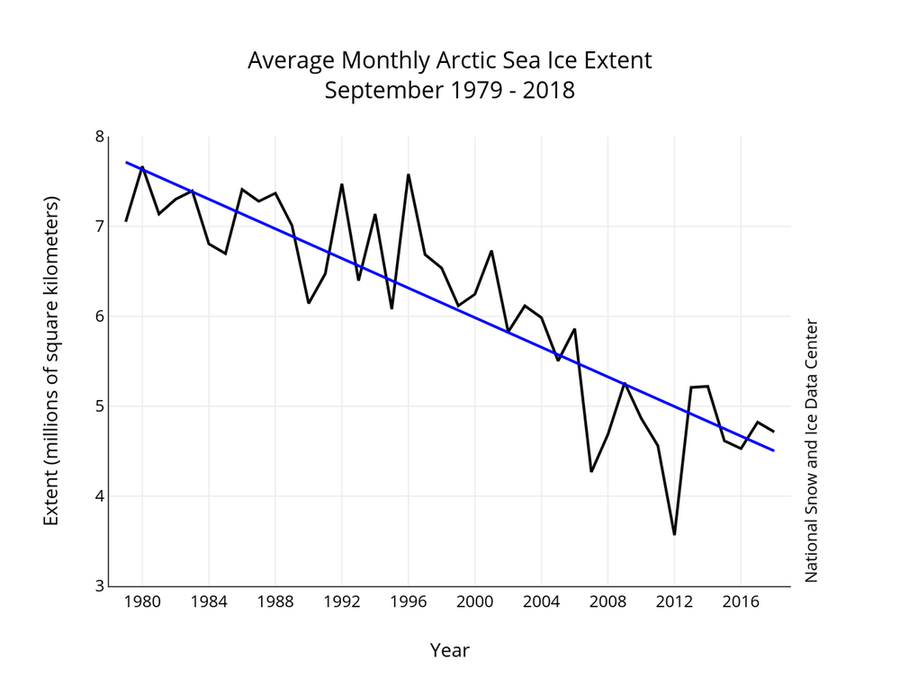

Average September Arctic sea ice extent from 1979 to 2018. Black line shows monthly average for each year; blue line shows the trend. National Snow and Ice Data Center

The Arctic is particularly sensitive to human driven climate change. We know the decrease in sea ice is due to both the warming of the Arctic (air and ocean) and changing wind patterns that break up the ice cover.

But there are also amplifying mechanisms or “feedback” mechanisms, in which one natural process reinforces another. Their role in the decrease of sea ice is hard to predict. We now know winter storms in the Arctic contribute to these feedback mechanisms.

More storms ahead

Arctic winter storms are increasing in frequency and this is likely due to climate change.

With the thinner Arctic sea ice cover and shallower warmer water in the Arctic Ocean, the mechanisms we observed during the winter storms will likely strengthen and the overall impact of winter storms on Arctic ice is likely to increase in the future.

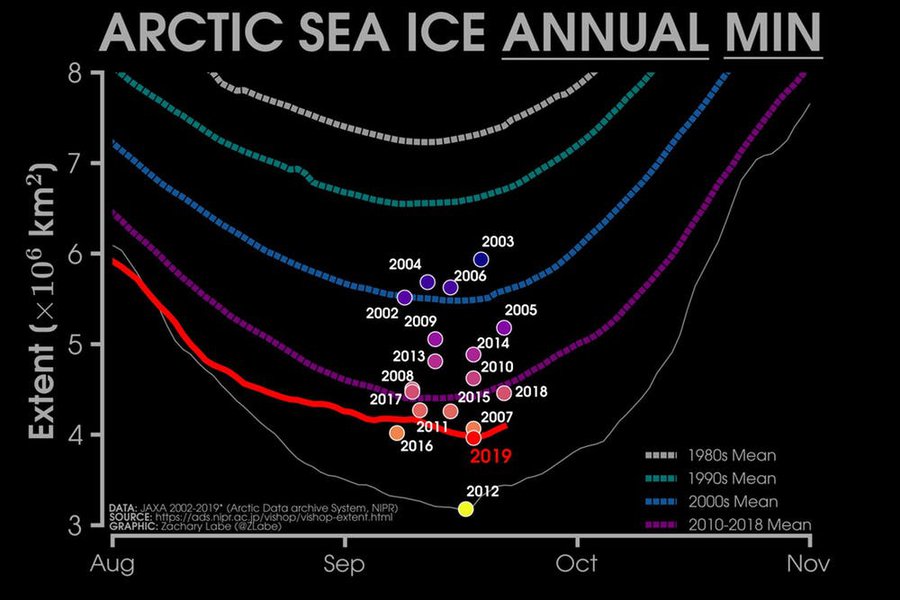

Two weeks ago, the Arctic sea ice reached its minimum extent for 2019, after another winter of intense winter storms. The minimum ice extent was effectively tied for second lowest since modern record-keeping began in the late 1970s, along with 2007 and 2016, reinforcing the long-term downward trend in Arctic ice extent. Arctic sea ice has been declining for at least 40 years, and amplifying mechanisms such as the winter storms are accelerating this retreat.

Arctic sea ice extent just reached its annual minimum extent for 2019 on September 18. This season was a tie for the 2nd lowest on record, along with 2007 and 2016 and behind 2012, which holds the overall record minimum. Zack Labe (@ZLabe)

As highlighted in the recent IPCC Ocean and Cryopshere report, these changes in September sea ice are likely unprecedented for at least 1,000 years.

Remember also that changes in the Arctic don’t just affect the immediate region: Arctic warming has been linked to the polar vortex, and weather extremes across central Europe and north America.

As we start taking into account feedback mechanisms like the winter storms, our predictions for the first Arctic sea ice free summer are indicating it will likely happen before 2050.

This article was originally published on The Conversation