The Gypsy cuckoo bumble bee may be the proverbial canary in the coalmine of North American bumble bee health.

This is according to Syd Cannings, a Yukon-based species at risk biologist with Environment and Climate Change Canada, and lead author of a recently-released strategy to help the endangered insect recover.

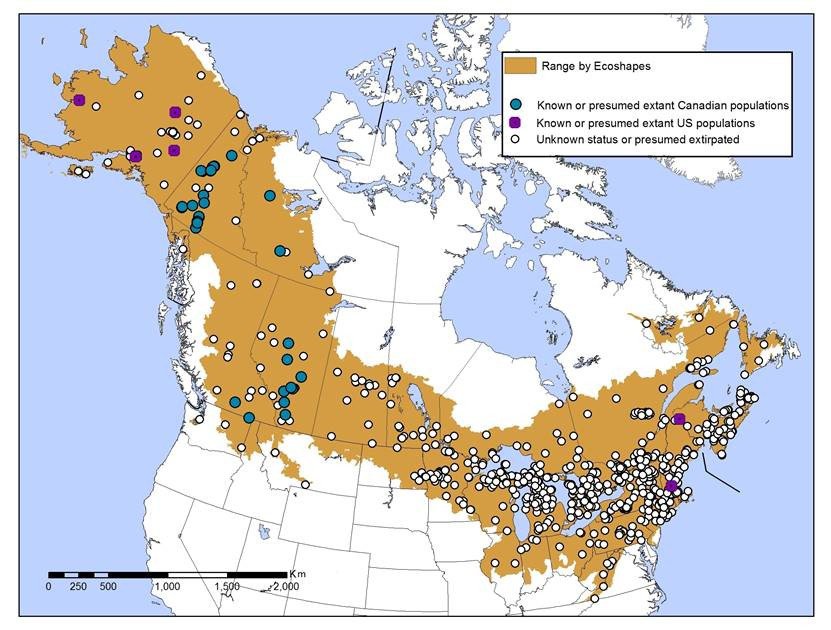

Unlike honey bees, which were introduced by European settlers, bumble bees are native to North America, with species found across the continent. The Gypsy cuckoo bumble bee (please see sidebar) has traditionally been found in nearly all parts of Canada and Alaska, with a range extending into the Northern United States. Its unusual parasitic reproduction cycle means it could be an ideal indicator of overall bumble bee health.

In May 2014, the Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada officially classed the G. cuckoo bumble bee (Bombus bohemicus) as Endangered, and in 2018 added it to the Species at Risk Act (SARA), citing an inferred decline in abundance of of more than fifty per cent over the last decade, with many populations presumed eradicated.

How severely populations have dropped varies depending on region, but the decline is especially severe in some southern populations, particularly in eastern Canada. Northern populations, such as those in the Yukon, seem to be faring slightly better, notes Cannings.

This dramatic population decline, however, is more than just bad news for the G. cuckoo bumble bees–it’s an indication of the general health of numerous bumble bee species across Canada.

Although the G. cuckoo bumble bee might look like any other bumble bee–large bodied, fluffy, brightly coloured–their cuddly exterior belies an ingenious reproductive strategy; the species is a “specialist nest parasite,” meaning they invade the hives of other bumble bee species and use the colony to care for their own young.

Specifically, the G. cuckoo bumble bee parasitizes only nests that belong to bumble bees within the subgenus Bombus–-to which it also belongs–and its own decline is the largely the result of similar population downturns in its three main host species; the rusty‑patched bumble bee (B. affinis), the yellow-banded bumble bee (B. terricola), and the Western bumble bee (B. occidentalis).

This high-degree of selectivity means, as the recovery report notes, that the G. cuckoo bumble bee’s ability to bounce back from its precipitous decline, “largely depends on the continued survival and/or recovery of its hosts.”

Historic distribution of G. cuckoo bumble bee, with noted or unknown extirpated and extant populations. From the 2022 Gypsy Cuckoo Bumble Bee (Bombus bohemicus) recovery strategy proposal.

Therefore, Cannings says, a downturn in bumble bee populations overall is the real cause of the decline in this specific species–and something, more largely, to be concerned about.

So what’s the matter with the other bumble bees?

A number of things, as it turns out; the report found that ”the primary threats affecting those (host) species are numerous and not completely understood.” Climate change is one such threat, as is the use of insecticides and other pesticides, and habitat loss through intensification of agriculture and urbanization.

Another big one, says Cannings, is diseases passed on from other bees, those used to pollinate greenhouses. As noted, honey bees – which are the bees people tend to associate with ‘colony collapse’ and want to “save” when they think of saving bees–aren’t native to North America; they’re essentially introduced livestock, and don’t do well overwintering in Canada outside of their domesticated hives tended by beekeepers.

A Western bumble bee (B. occidentalis). This species has been especially hard hit in southern British Columbia. CRED:Jeremy Gatten

Bumble bees, by contrast, have adapted to survive Canadian winters in the wild, and are some of the most important pollinators for North American plants, especially berries, which need what Cannings calls “buzz” pollination–a speciality of Bombus bumble bee species. The flowers of the plants in the blueberry family, for example, have their pollen enclosed in tubes–to get to it, a bee of any species has to shake the flower, which bumbles are far better adapted to do than honey bees.

“It’s cute,” says Cannings. “The flowers are so tiny and the bees are so big, but the flowers need that good shake to get the pollen out and pollinate the others…honeybees can go there and suck the nectar and and try to gather the pollen but they're not going to be very efficient about it.”

As a result, most North American fruits like blueberries and raspberries–especially in the Yukon, Cannings notes–are better pollinated by bumble bees. This has resulted in attempts to semi-domestic them as pollinators for greenhouse use, which could actually be leading to their decline (and, in turn, the decline of the G. cuckoo bumble bee).

“They raised them just like honey bees,” he says, meaning the bees were cared for in small, highly controlled environments that pushed individuals closely together, conditions that are much more condensed than they would be in the wild.

A G. cuckoo bumble bee feeding in Miles Canyon, near Whitehorse, Yukon. CRED: Syd Cannings

“They have little boxes full of bumble bee nests with Queens and their workers, and they go around and pollinate your tomatoes and your cucumbers and your peppers–and those bees all live in tight quarters inside a greenhouse. It’s like they're in a very squashed-in apartment in the city,” Cannings explains. “So when bees get sick… everybody gets sick together.”

Inventiably, some of these unhealthy, infected domesticated bumble bees escape their enclosure and feed on flowers wild bumbles are feeding on, infecting them and introducing pathogens to wild populations they might not have otherwise been exposed to. These diseases can be spread not only between bumble bee species, but to bumble bees from domesticated honey bees.

This evidence is circumstantial–but it’s a hell of a circumstance; as greenhouses using bumblebee bees as pollinators increased in the 1990’s, the amount of parasites found in wild populations “increase[d] dramatically,” Cannings says.

At the same time, populations of Bombus bumble bees began to decline by up to 90 per cent in some areas–and, with it, the decline of the G.cuckoo bumble bee.

Because it relies on other bumble bees to reproduce, G. cuckoo bumble bee populations are naturally dependant on the density and health of its host species, who in turn require a suite of floral resources to support colony growth, especially pollen and nectar need, which must be abundant and available.

The reproductive strategy the G. cuckoo bumble bee employs–is actually not uncommon in nature, nor is it (and other forms of parasitism) uncommon among Hymenoptera, the large order of insects to which all species of bees and wasps, (and ants), belong.

“There are cuckoo bumblebees and there are cuckoo bees, but the basic thing is that a number of bee (species) cheat the system by using other bees to rear their young, like a cow bird or a cuckoo,” says Cannings. “And so this does that–it takes over the nest of other bumblebees…. And get the workers in the nest to tend their young, rather than the young (their own) they should be tending.”

To accomplish this, the G. cuckoo bumble bee uses a combination of opportunism, stealth and –if necessary–force. How G. cuckoo bumble bees undertake this reproductive sleight of hand is a revealing look into the way bumble bees survive in North America–and part of what makes them so vulnerable in the first place.

So, if G. cuckoo bumble bees kill off the host nest of the other bumble bees they parasitize, and all the bumble bees are in trouble, one might be inclined to naturally ask: why make an effort to save the G. Cuckoo Bumble bee, which actively preys on and destroys the nests of other species?

MacKay’s Western bumble bee (Bombus occidentalis mckayi) the northern subspecies of the Western bumble bee often found in the Yukon, feeding on a clover blossom on the Haines Road, between Alaska and Haines Junction, Yukon. CRED: Syd Cannings

There’s two answers to that, says Cannings. One, is that every species has “inherent value” simply in existing. Secondly, the G. Cuckoo bumble bee is an indicator species, and everything that can be done to help it recover is ultimately about helping its host species recover; what’s good for G. cuckoo is really what’s good for all Bombus bumble bees.

Generally speaking, there are things which lay people can do to make all bumble bees healthier, says Cannings, including making “greenhouse bumble bees happier” and more resistant to disease by providing less dense environments and making sure they don’t escape to interact with wild populations. People should also avoid the use of pesticides, especially neonicotinoid pesticides, “unless you really really have to and only use them when you've got a problem.”

Yards can also be made friendlier for bumblebees, by adding flowering plants for them to feed on, and leaving wild, natural patches. Bumble bees nest on the ground, and need these spaces to find empty burrows dug by rabbits, mice and voles.

“We (biologists) are all saying ‘these are the things that will help bumble bees,” regardless of species, he adds.