Eddy Carmack, a Senior Research Scientist Emeritus for the Department of Fisheries and Oceans, has been conducting research in high-latitude rivers, lakes and seas spanning from the Antarctic to the Arctic and from the Yukon to Siberia for over 50 years. He recently had a conversation with Gail Whiteman, the Director of the Pentland Centre for Sustainability in Business at Lancaster University. Gail is one of the founders of Arctic Basecamp, a group of leading scientists working to communicate to global leaders why action needs to be taken to address the dramatic changes occurring in the Arctic as a result of anthropogenic climate change.

GW: Now, Eddy, you're a legend in arctic science, so could you tell a little bit about your expertise?

EC: Well Gail, let’s play down the legend part. I would say my expertise is longevity. I've been working in the Arctic for almost five decades now, so this whole issue about whether or not the arctic is changing, or how rapidly it is changing, has become rather personal You don't need fancy, scientific instruments, and you don't need satellites to see the difference. You almost just need to see it and feel it.

GW: So tell me about the differences. What have you seen in five decades?

EC: Well, I started out as a graduate student at the University of Washington, for example, and I joined a little team of two other students to go to the Canadian Arctic to measure currents flowing from the Arctic Ocean out into the North Atlantic, and we were in an ice camp in the far north. We were sitting on rigid, hard, cold ice that was more than two meters thick, and I know if I went to do that today in a tent I would be swept away and would not survive.

So the whole landscape is changing quickly. The Arctic is visibly greener. Satellites are noting this, but just flying over it it's something you're going to see. These are the kind of things you become aware of.

GW: And why is that change happening? What's driving the change?

EC: Well we are. I don't think the debate is there anymore. The arguments date back, again, decades, but the voices weren't heard. I know that in the middle part of the 1980s I was working with two real legends of arctic science, Knut Aagaard and Norbert Untersteiner, and we thought it was important to start measuring the thickness of the ice.

Norbert had developed an upward looking sonar that you would moor to the ocean floor and it would send an acoustic signal upward, just like a depth sounder on a boat only upside down, and it would start recording how thick the ice is. Knut was a pioneer in developing under ice moorings. We struggled for about five years to keep that project going. The data coming back indicated a trend, but in the early 1990s there just was simply no interest in the decline of Arctic sea ice, so that little time series ended.

Luckily it has been picked up by collaborative efforts with the Woods Hole Institute and the Institute of Ocean Sciences, so these measurements are now being continued.

This non-linear collection of events is happening faster in the Arctic than it is happening elsewhere, so to a scientist this says if you want to understand the future, it's already arrived in the Arctic.

Eddy Carmack

GW: And how rigorous is the science behind this measurement of Arctic change?

EC: Well, being a participant, I would have to say very rigorous; we're looking under every rock, into every corner. Arctic change is not just the ice retreating. As the ice retreats there's a whole cascade of effects that go with it. So I think the scientific community is spreading out and trying to understand how this impacts weather, how it impacts trade, how it impacts travel, how it's changing the ecosystem, how the underlying ocean is both responding to the ice retreat and now causing it to happen more quickly.

The ocean itself contains a tremendous amount of heat below the surface layers of cold and relatively fresh water; layers that kept the heat in and away from direct contact with the ice. Now, in some places, these layers are starting to weaken, and more heat is coming up to melt ice. This sleepy little ocean is starting to wake up. Along with the heat coming up, then you have nutrients coming up, and so the biology is changing. So all of these things are conspiring, you might say, to bring about what is collectively called Arctic change.

GW: And why does Arctic change matter?

EC: Well, I could get philosophical here. The arctic is changing faster than any other part of the planet, and that's a phrase that rolls off people's tongues quite easily. That is confirmed. The measurements are there to back that up. But this change, as I mentioned, is not just a straightforward linear warming. All the pieces are connected. It's a non-linear system that's subject to surprise, to tipping points, to catastrophes, to collapses, all the things that mathematical dynamicists love to work with.

It matters because this non-linear collection of events is happening faster in the Arctic than it is happening elsewhere, so to a scientist this says if you want to understand the future, it's already arrived in the Arctic. So let's double down on our efforts to understand the consequences of Arctic change and drive ourselves into a position where we can better predict or anticipate what will happen elsewhere on the globe.

Homes sit smoldering after Hurricane Sandy on October 30, 2012. There is mounting evidence that as the Arctic warms, the likeliehood and severity of extreme weather events in the mid-latitudes will increase. Photo by Mishela/Adobe Stock

GW: And why should somebody living south of the Arctic care about Arctic summer sea ice or about the health of the Arctic Ocean?

EC: Because it's happening faster there we can begin to understand the consequences to whole ecosystems. There is mounting evidence that the Arctic doesn't have a wall around it. It's connected to the mid-latitudes, and the mid-latitudes and the tropical low-latitudes are where most of the people live. Now there's concern that there's strong interaction between the arctic sea ice retreat and weather events that are happening elsewhere on the planet.

GW: So if I'm talking to global decision makers, I sometimes say the Arctic is a barometer of global risk. Do you think that's a fair statement?

EC: Of course it is. It's not only a barometer, Gail. It's a crystal ball, a looking glass, and we're not paying sufficient attention to the subtleties of change and the creeping changes that are occurring.

My field was originally physical oceanography, so I try to understand the formation of water masses, how the North Atlantic deep water formed, how Antarctic deep water formed, all of these movements of water, but it slowly kind of evolved into more interest in the ecosystems that are impacted by the physics.

Recently I've stumbled into the field of geology, which I think is becoming one of the most exciting fields in science right now. Over the past two or three decades, geologists have been developing new tools to look into this crystal ball and people are becoming more and more aware of creeping extinction. Things start eroding away at the bottom of our systems that lead to slow changes that lead to extinction.

These are well-established events in the geological record. They've been known for many, many, many years. But the events and consequences behind these extinctions are just coming out in the literature, how extinctions are involved with changes in the oxygen content of the atmosphere, or changes in volcanic activity that's changed the carbon dioxide, or changes in ocean acidification and erosion, the changes in sea level having a major impact on the chemistry of the oceans.

All of these things act to alter what you might want to call the variable of life, the amount of oxygen in the ocean, or the chemistry or the nutrients that are involved, the acidification. These experiments, if you want to call them that, have been played out many, many times in the past, and when they occur they can eradicate 90% of life on Earth.

So I don't think it's irresponsible to start talking about the processes that are occurring today and to compare them to what the geologists have observed in the past, to examine the urgency of what we're doing. I'd like to go a little further there. I think it was the philosopher George Santayana who's credited with saying that "he who ignores history is doomed to repeat it.” But you could also say that he who ignores the fossil record is doomed to join it. And I think we ought to get off our butts and start worrying about what are we really doing to the next generation. And let's stop mouthing about caring for our grandchildren, and do something quickly about it.

I think what our work is showing, together with many, many other scientists, is that because of the interconnections between the Arctic and the rest of the world, those impacts could be vast.

Gail Whiteman

EC: What about you Gail? You've been a powerhouse in trying to get this message out. And do you think that this message is resonating with leaders of the world?

GW: I think one of the things I've seen with the Arctic Basecamp event that we've hosted at Davos for two years running, is that world leaders are hungry for knowledge about global risk. And I think they are starting to wake up to the fact that the Arctic, and Arctic change, poses tremendous global risk for economies in countries around the world.

And I think that's a new narrative on the Arctic. I think, in the past, people were worried that arctic change was bad news for the polar bear, or bad news for local people; maybe good news for shipping companies, and oil and gas extraction. And I think what our work is showing, together with many, many other scientists, is that because of the interconnections between the Arctic and the rest of the world, those impacts could be vast.

They could be negative and they could be extremely extensive, if I put my economic hat on. So I think we are definitely starting to do that, in conjunction with many others, so I think the Arctic Basecamp initiative is a way of taking science out of the silo and trying to talk in language that people with power can understand. And I think that is about global risk.

EC: Well that's a good point, bringing science out of the silo. We scientists are comfortable in our silos, but it's also very difficult to get out of our silos, and get the message across. So this coordinated effort, I think, is really important that we're talking about here.

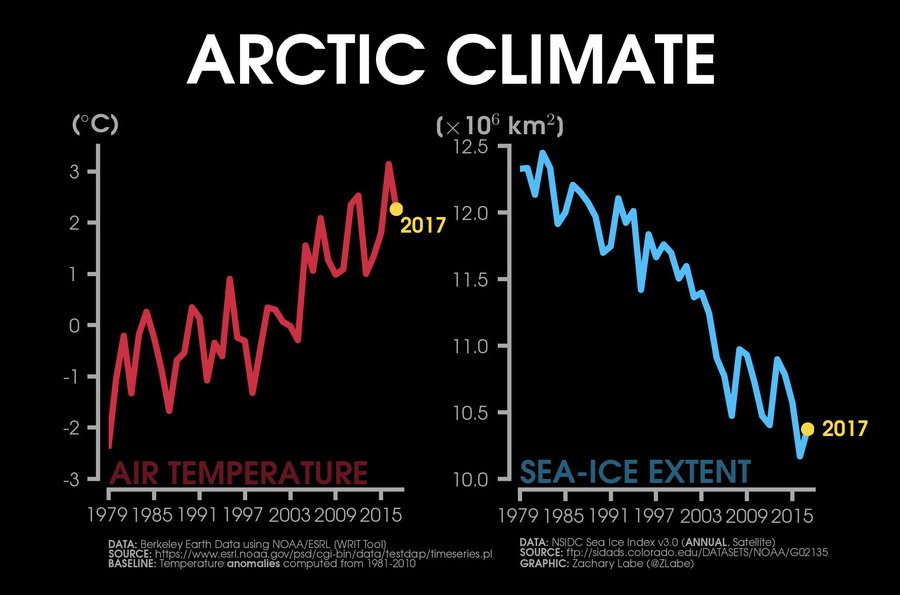

Changes in annual mean Arctic sea ice extent (NSIDC, Sea Ice Index v3) and air temperature anomalies (Berkeley Earth Surface Temperature; BEST) over the satellite era. BEST is available from 1850 to 2017 at http://berkeleyearth.org/data/. Updated 8/20/2018. Graphic by Zachary Labe.

GW: Well I think, Eddy, you were one of the first people to do that when we went up to the Canadian Archipelago on the Louis St-Laurent. I think your idea of having experiential dialogues with multiple kinds of people, right in the Arctic, was ground-breaking. And maybe you could tell us a little bit more about that idea, and what you saw happen by bringing together leaders from different sectors and showing them Arctic change firsthand.

EC: This is what we like to call the "philosophers cruise." And it started, really, in the late '90s, early 2000s, together with a dear friend and colleague, Marty Bergmann. Marty suggested this, and I had a program that was sending the Louis S. St-Laurent, which is Canada's largest icebreaker, from the east coast of Canada through the Northwest Passage, and into the Canada Basin to start this long-term climate-monitoring program.

And at that time, believe it or not, there was no interest whatsoever in the Arctic. We were trying to get administrators and leaders and bureaucrats from Ottawa interested in the Arctic. Here was a free trip on an icebreaker, through the ice, past the polar bears to the fabled Northwest Passage. And most people were too busy to take the time.

But the philosophy behind the philosophers cruise was to put scientists together, not just the scientists in our own program, but scientists from England, or Norway, or elsewhere around the world together on a ship with business leaders and senior government leaders and into a kind of Arctic boot camp. And each person was required to talk for an hour about their own field of interest. So there's no straight agenda other than "we listen to each other, and try to take something home from the experience that we could put into practice."

And there have been a number of spinoffs from this that are carrying on today. A lot of ideas were generated and you can see them scattered around, in various places.

Paul Wassmann in Norway is engaging in a similar effort, where he's inviting influential people aboard a Norwegian icebreaker for dialogue and discussion, and to experience what the Arctic really is. So more of these are certainly desirable. And it's a lot different than getting on a cruise ship and being told what you're supposed to be excited about. It's about getting a small group of people together to really, really knuckle down and generate ideas that would improve the way we're doing business, both in science and in business-business.

The R/V Martin Bergmann, a research vessel owned and operated by the Arctic Research Foundation, in Bathurst Inlet, Nunavut. For the past seven years, this vessel has been supporting multidisciplinary science research in the Northwest Passage. Photo by Yves Bernard.

EC: We have to bridge knowledge through those scales. And one example is the work we're doing out of Cambridge Bay in Nunavut right now, with the Arctic Research Foundation. And it's a local scale. It's a small part of the Northwest Passage that we wish to understand physical and biological coupling, within this area.

We need to expand that to understand how the human dimension is connected to the ecosystem that is, in turn, the result of this physical-biological coupling. And then what does this mean? Or how can this regional knowledge be scaled up to understanding that all of the Canadian Northwest Passage, all of the Canadian archipelago, and finally to the Pan-Arctic and global.

We've got all these pieces that we're studying, like little pieces of a puzzle. Now we've got to put it together into a coherent piece that becomes a vision, a shared understanding of the pan-arctic system. And then we move on through modeling, satellite observations, dialogue, discussion and experiments so we can couple the Arctic to the global system, both in the atmosphere through weather patterns, through storm tracks, through disruptions of the jet stream; to impacts that the loss of sea ice may have on droughts, or extreme cold weather events, or hurricane sizes, or all of these things.

But putting these things together in a meaningful way, and not just a "by-chance correlation," that the Arctic is changing, and that hurricanes are getting stronger and a whole lot wetter. We need to understand, why is that? How do these processes occur across these scales, to make what we're seeing understandable?

We really need a call to action to global leaders to see if they are able to accelerate climate action. We need to get towards a low-carbon economy globally.

Gail Whiteman

GW: So what I am interested in as a social scientist is to take all of that natural science understanding, both of local, regional, and then global links from arctic change. And I want to try and understand the economic price tag. Who is going to pay for those costs? And I think a key area that we need to more research on is to say, how does Arctic change affect our ability globally to deliver on the sustainable development goals?

So the world, the UN, they signed up new goals. They're great aspirational targets for 2030. And there's a lot of different aspirational targets for 2030, and there's a lot of different types of organizations, businesses, governments and civil society groups working together to try and deliver those. I think there's very little appreciation right now on how Arctic change, especially if it accelerates or we reach some tipping points, how that will affect our ability to meet those goals. I think we need to understand not just how the Arctic will change inside the Arctic region, but also how it will really pose those threats to those very important SDGs. And I think we really need a call to action to global leaders to see if they are able to accelerate climate action. We need to get towards a low-carbon economy globally.

I guess what gives me hope is that we've got leaders out there like Governor Brown of the State of California. He's hosting this amazing summit in California to turbocharge global carbon action. I'm encouraged that people like him, Christiana Figueres, of course, former secretary of the UNFCCC, Mike Bloomberg, and many, many, many others are actually standing up and saying, "Regardless of what some administrations may say, we are moving forward, and we have to act fast." I think the science that we bring on Arctic change, and then when we link it to the global processes like the SDGs, I think it shows a clear case that these people have to act fast, that their cause is just, it's needed, and we need to go as fast as possible, and we need to get new sectors helping.

Where's the high-tech sector? What can Facebook, Google do to help slow down Arctic change? You know I'm not sure they're paying attention to Arctic summer sea ice melt, but they should be. How can they enter into our world on a minute-by-minute, second-by-second basis? How can they help us actually address the threats that are driving Arctic change and that will actually drive change for us? So that's a big task and it's not what I'm going to do alone, but I just want to trigger some of those discussions.

Mary Avalak of Cambridge Bay, Nunavut, carries an Arctic Char back to her summer cabin for a family meal. According to Eddy Carmack, "Sustainable goals are not going to be achieved unless they start right in every individual family in the Canadian Arctic and building out." Photo by Zachary Prong.

EC: You're talking about things happening at a pretty high level with the names that you're talking about. But it all starts in the communities of the North. It starts in the families. Sustainable goals are not going to be achieved unless they start right in every individual family in the Canadian Arctic and building out. So I kind of see we need to put those sustainable goals out there as real goals, identifiable goals. Whenever anyone at any level makes a decision, he or she is asking, "Is this decision, do I turn left, do I turn right, which decision takes me closer to those sustainable goals?" or which at another level may say, "Which decision takes me to a better showing in the stock market or does it help level the grounds that my granddaughter must cross?" Because the sustainable goals are not just our goals, they're goals that have to be instilled in the children and the generations, because this is a long-term game, and it's serious.

GW: Exactly. You know what worries me is that there are decisions made today this year, next year, that will make that future hard to come by. I think that kind of a good rule of thumb is if you're faced with a decision, if it doesn't help bend the emissions curve by 2020, then that's not the right decision. I would say that to my own family, but I would also say that to world leaders like Prime Minister Trudeau. I have to say as a Canadian, as a social scientist working on climate change, I was pretty shocked to see the decision on the Kinder Morgan pipeline as a new purchase by the government of Canada. I think that's not a decision that would help bend the emissions curve by 2020. Wearing my Arctic change and global risk hat, I would then say that that is the wrong decision. It certainly makes short-term economic sense for Canada perhaps, but it is not a decision that makes sense for the rest of the world.

EC: Well, that's true. These decisions have to be based on the long-game. Otherwise, the consequences will mount up. You can make these little tiny decisions, and cut corners, and compromises, but they add up, and they will always come back. So a clear path, a steady path at this time is quite urgently needed.

I think we need to infuse a bit of morality into this question of global change, of Arctic change, of the risk to the future.

Eddy Carmack

GW: What gives you hope, Eddy?

EC: I think it's instilled in me to be optimistic. I think we can solve these problems. They're incredibly complicated because there's so many world leaders now who are doing everything they can to upend global sustainability goals and send them to the garbage can because short-term power, political and economic gains are more important to them, and they're gaining traction. That is a fearsome thing to my mind.

So I think we need to infuse a bit of morality into this question of global change, of Arctic change, of the risk to the future. Its first impact may not be the complete eradication of life as we know it through the massive extinction. I've talked a little bit about the threat of extinction, and that we're making the oceans more acidic, and the Arctic is a prime site for that process. We're drawing oxygen out of the oceans at an alarming rate. That's because the warming, the doubling of temperature, more or less quadruples the drawdown of oxygen by bacteria. There's large areas of the ocean that are already hypoxic, as they say, with oxygen levels really too low for fish to swim around in.

So these are concerns, but I think the first casualty of ocean change, Arctic change, is going to be the economic structure. When you saw the damage that just a little old collapse in the stock market in 2008 could do to the world order, and how the ramifications are still resounding as we see demagogues sprouting up everywhere, capitalizing on the fear and the mistrust that was created during that event. I think the economic system is definitely vulnerable to the changes that we're seeing in systems globally, and the Arctic is a huge player in this, and it could be an important point of pressure to the global system.