At the end of World War I, after four years of unimaginable man-made destruction, a swiftly killing virus travelled the planet. Up to one hundred million people perished in the most lethal pandemic in recorded history, the so-called “Spanish” influenza. More than half those who died were young adults aged between twenty and forty.

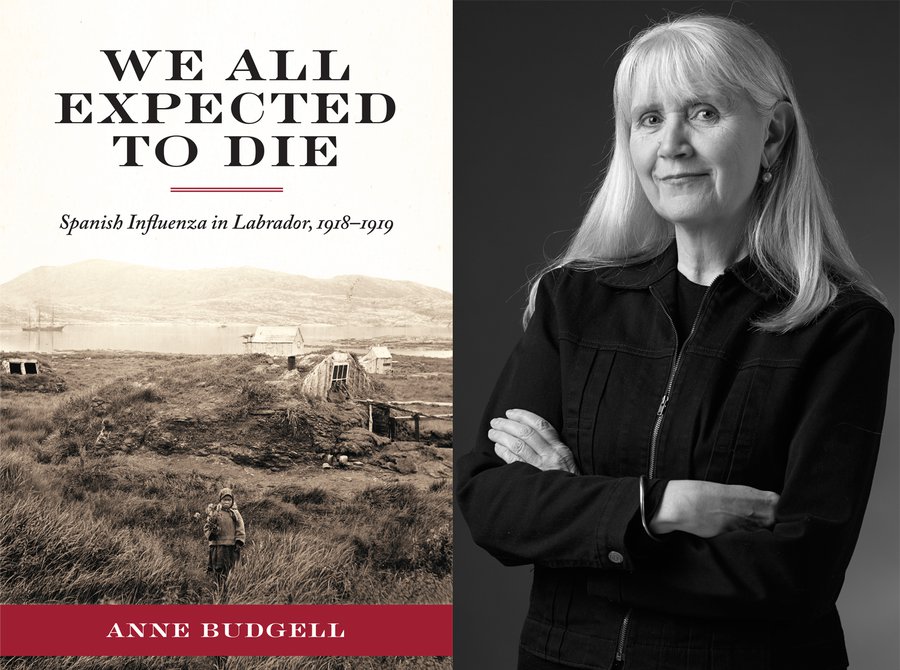

Nowhere on earth was the flu more deadly than in isolated settlements on the far northeastern coast of North America. In We All Expected to Die: Spanish Influenza in Labrador, 1918–1919, now availble from ISER Books, Anne Budgell reconstructs the horrific impact of the pandemic in hard-hit Labrador locations, such as the Inuit villages of Okak and Hebron where the mortality rate was 71%.

In the following excerpt, Budgell writes about how filth, sin, backwardness, and immorality among the Inuit were cited as explanations for this tragedy.

Author photo by Ned Pratt.

One cannot help wondering sometimes whether the Eskimos are hastening to extinction.

—Hopedale Annual Report, 1917−18

If the Moravian missionaries were honest, they would have had to admit their view of the Inuit “hastening to extinction” came up rather often. Death caused by epidemic sickness was a frequent topic in reports from the north coast, often accompanied by a concluding remark that the Inuit were at least in decline, if not on the road to extinction. In 1965, anthropologist Diamond Jenness summarized the disease outbreaks among Labrador Inuit in the years between 1774 and 1885 on a list that showed 32 deaths from measles in 1828, 18 deaths from “malignant cough” in 1830, “many” deaths from influenza in 1842, 59 deaths from an unknown disease in 1855−56, 50 deaths from either influenza or typhoid in 1862, over 100 deaths from whooping cough in 1876, large numbers of deaths from whooping cough and measles between 1880 and 1882, and many deaths from measles in 1885. Jenness figured only “their high birth-rate, and such aid as the missionaries could provide, saved them from being exterminated” by disease.

The pandemic flu of 1918 claimed more lives than any earlier event, but was preceded by decades of many other outbreaks of deadly illness in the years before widespread vaccination and antibiotic drugs. If death on this scale had happened in Newfoundland, or Canada, or England, a public health emergency would probably have been declared, but these were the Labrador “Eskimos,” who were fulfilling the prediction of the missionaries that they would soon all be dead. It was a prevailing notion among the Moravians, who were not unique in this belief.

As Patrick Brantlinger has shown in his thorough survey of 200 years’ worth of reports, studies, literature, and memoirs, written by European explorers, colonists, writers, officials, missionaries, humanitarians, and anthropologists, “extinction discourse” was the ruling theme. Brantlinger tracked the practice of “hierarchizing” the races, “with the white, European, Germanic, or Anglo-Saxon race at the pinnacle of progress and civilization” and the “dark races” below in various degrees of inferiority. For missionaries, it was their task “to save at least the souls of the last members of the perishing races.” For anthropologists, it was urgent to learn as much as possible about the people before they vanished. For explorers and colonists, it excused taking land from people who were not farmers, owned “nothing,” and were doomed anyway. People like the Inuit, who had lived for millennia in a harsh environment, were given no credit for their skills in adaptation, in developing specialized clothing, tools, kayaks, sleds, and houses of sod or snow. Their culture was “primitive.” They were considered uncivilized.

Northern Labrador, where the Moravian Mission had been established for almost 150 years, must have been considered a missionary success story, if “civilizing” and “Christianizing” were the goals. These were educated Inuit, complimented for how literate they were, or how well they could play musical instruments, but flaws would always be found. Governor MacGregor visited Nain in 1905 and spoke at the church, telling people first that they should obey the self-sacrificing missionaries, who “could be much more comfortable, and could earn much more money, if they stayed home instead of coming to Labrador.” He advised them to listen to Drs. Hutton and Grenfell and sounded a warning about infant mortality:

I have been very much surprised and pleased to see how well off you appear to be. You all of you are well clothed, and you all appear to be well fed. I have been very much delighted to hear, both at Nain and at all the stations, that all the grown-up Innuit [sic] can read, and very nearly all can write as well. Indeed, all round I am very much pleased with your condition. But there are many things yet to be done. One thing troubles me very much. I see your country is very large, and your people are few, and yet so many of your children die. It would be very sad indeed to see your race grow smaller.

Inuit people could not be faulted for being resistant to “improvement” or unwilling to “learn the arts of civilization,” criticisms made of Native Americans by some commentators in the nineteenth century who blamed them for their own annihilation. But as will be seen in Labrador examples from 1894 to 1916, those pronouncing on the reasons for shocking death rates from disease, or high infant mortality, would still cite filth, sin, backwardness, and immorality as roots of the problem. People were blamed for not being clean enough, or devout enough, or intelligent enough to survive outbreaks of disease.

...

If the deaths of nearly 400 people from measles, typhoid, and influenza between 1894 and 1916 were to be understood as the “Lord speaking very plainly,” a hard and cruel message had been sent. When the flu struck the coast in 1918, those who believed God administered punishment by inflicting killing disease would surely have been trying to understand what unforgivable sins they had committed to draw down such wrath.

Anne Budgell is a former radio and television journalist. She wrote and co-directed the NFB short documentary The Last Days of Okak and is the author of Dear Everybody: A Woman’s Journey from Park Avenue to a Labrador Trap Line.

You can watch The Last Days of Okak below.