Summers in Nunavut shower an explosion of beauty and colour on a landscape that has known only snow and ice for much of the year. With the return of the warmer weather comes the re-appearance of wildlife and birds contradicting the myth that the Arctic is a place devoid of life or character. The land’s unique character is enhanced by long hours of daylight, which provide exaggerated dawns and dusks with their soft colours extending seemingly forever, a dreamscape for any painter or photographer.

As my time living in the North grew longer, I spent more of my summers using Iqaluit as a springboard to explore Nunavut, visiting historic sites and northern parks and looking for wildlife, all the while taking pictures along the way. One summer Mosha Akavak and his son Joshua and I went looking for walruses and bears along the south coast of Baffin Island. Mosha is an experienced hunter who is constantly out on the land and Joshua wanted to get his first walrus, so our goals coincided nicely. The Akavak family is originally from Kimmirut, about 100 km southwest of Iqaluit, and since Mosha planned to spend August in his hometown one summer, we decided to set out from there.

Joshua poised to harpoon his first walrus.

I could have taken the daily scheduled flight from Iqaluit across the Meta Incognita and Katannilik Park to Kimmirut but a friend who was part owner of a small Cessna plane needed to get his flying hours built up, so in exchange for buying the gas, I got not only a private flight over South Baffin but the feeling of unbelievable privilege! Once in Kimmirut we stocked up Mosha’s boat with gas and supplies and left on the high tide for a trip along the coast, going east along Hudson Strait.

Over the next couple of days, we explored bays and inlets looking for wildlife. We fished for Arctic char and searched for goose eggs because, when the two are cooked up together in butter for supper they are, well, mamaqtuq! We even had a night visitor, a wolf, who must have thought he was invited to dinner and who sat patiently near our tent for half an hour before realizing the kitchen was closed.

Time to butcher.

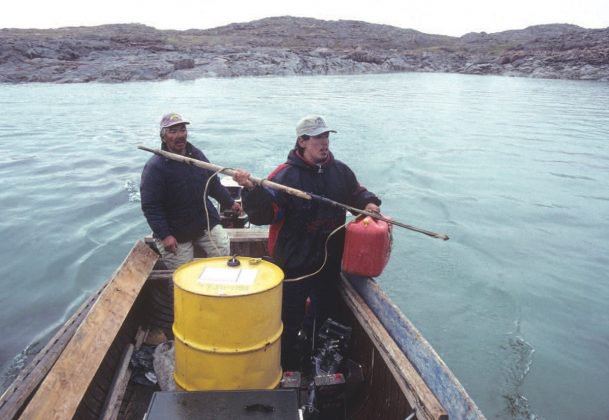

On day three, Mosha took the boat down a bay which stemmed from a river at the far end. Near that river was what we had come for, a small herd of walruses, watching us with their red-veined eyes. Mosha positioned the boat to keep them near the mouth of the river and suggested we should have something to eat as the hunt would come later. As the tide went down, he eased the boat towards the animals, slowly pushing them back towards the river. When the tide got to its lowest, the walrus found themselves stranded among the rocks and low river water and could not escape. Joshua’s time had come. He shot one walrus and immediately harpooned it, using a five-gallon jerry can to serve as a float.

With just enough water available to manoeuvre the dead animal out from the rocks, the two men tied it to the boat and pulled it into deeper water. After that, in true Inuit style, it was time for a cup of tea and some homemade bannock. With the daylight starting to lessen, the two Inuit towed the 1,000-kg animal across the bay to shore where it could be pulled up on the rocks to be butchered and cached. The skin would be made into strong rope, the blubber and meat would provide food for family and the ivory tusks would be sold or used for carving. As Inuit tradition has always dictated, nothing should go to waste.

Smoking the cache.

The next day, part of the walrus was cached under rocks to be collected the next winter, with heather thrown over the cache and set alight, a practice which sometimes helps drown the smell of the walrus and keeps hungry animals away. Then we loaded the boat with the rest of the carcass and headed for Kimmirut. On the way back, we came across a couple of bears, one on land and another in the water, with the latter providing the chance for us to get close to yet another majestic northern animal. For a while we cruised alongside the swimming bear taking pictures before heading back past the little bays and inlets towards Mosha’s home community.

Once back in town I reverted to my feeling of privilege and called up my personal aircraft. Soon afterwards the Cessna landed on Kimmirut’s short gravel runway and we flew back to Iqaluit through the quietness and soft colours of yet another of the North’s long evenings.

Nick Newbery taught in several communities in Nunavut from 1976-2005. The photos in this article are from Nick’s Arctic photo collection that can be found at www.newberyphotoarchives.ca and should be viewed from a historical perspective.