This article originally appeared in Yale E360.

There is a paradox at the heart of our changing climate. While the blanket of air close to the Earth’s surface is warming, most of the atmosphere above is becoming dramatically colder. The same gases that are warming the bottom few miles of air are cooling the much greater expanses above that stretch to the edge of space.

This paradox has long been predicted by climate modelers, but only recently quantified in detail by satellite sensors. The new findings are providing a definitive confirmation on one important issue, but at the same time raising other questions.

The good news for climate scientists is that the data on cooling aloft do more than confirm the accuracy of the models that identify surface warming as human-made. A new study published this month in the journal PNAS by veteran climate modeler Ben Santer of the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution found that it increased the strength of the “signal” of the human fingerprint of climate change fivefold, by reducing the interference “noise” from background natural variability. Sander says the finding is “incontrovertible.”

But the new discoveries about the scale of cooling aloft are leaving atmospheric physicists with new worries — about the safety of orbiting satellites, about the fate of the ozone layer, and about the potential of these rapid changes aloft to visit sudden and unanticipated turmoil on our weather below.

Increases in CO2 are now “manifest throughout the entire perceptible atmosphere,” a physicist says.

Until recently, scientists called the remote zones of the upper atmosphere the “ignorosphere” because they knew so little about them. So now that they know more, what are we learning, and should it reassure or alarm us?

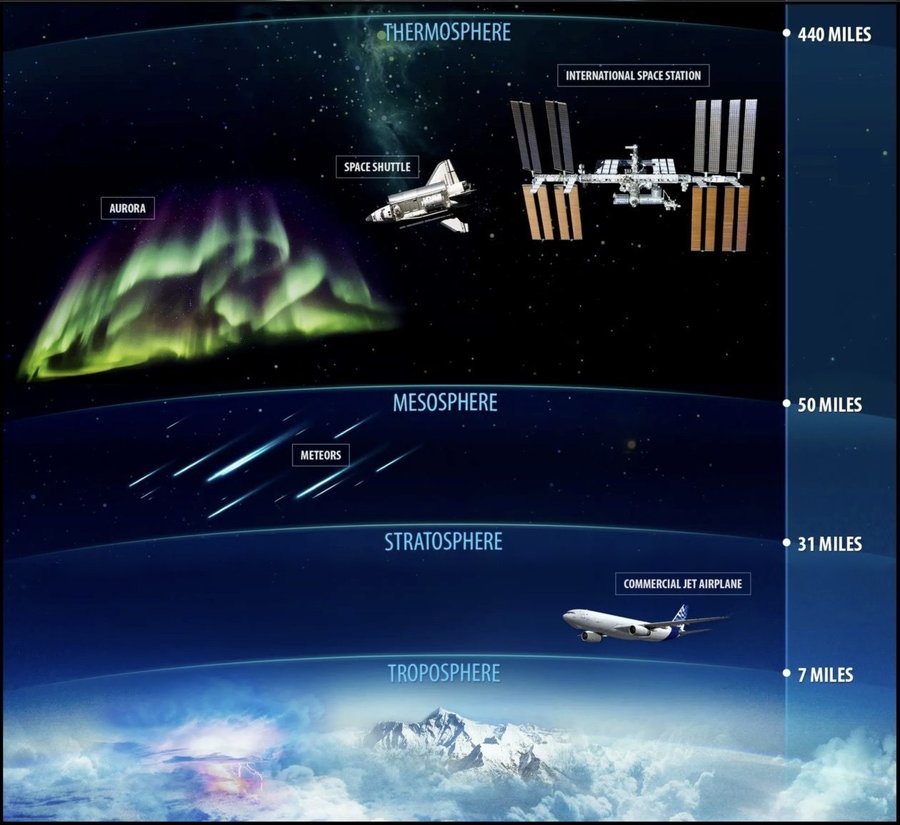

The Earth’s atmosphere has a number of layers. The region we know best, because it is where our weather happens, is the troposphere. This dense blanket of air five to nine miles thick contains 80 percent of the mass of the atmosphere but only a small fraction of its volume. Above it are wide open spaces of progressively less dense air. The stratosphere, which ends around 30 miles up, is followed by the mesosphere, which extends to 50 miles, and then the thermosphere, which reaches more than 400 miles up.

From below, these distant zones appear as placid and pristine blue sky. But in fact, they are buffeted by high winds and huge tides of rising and descending air that occasionally invade our troposphere. And the concern is that this already dynamic environment could change again as it is infiltrated by CO2 and other human-made chemicals that mess with the temperature, density, and chemistry of the air aloft.

Earth's atmospheric layers. NOAA / YALE ENVIRONMENT 360

Climate change is almost always thought about in terms of the lowest regions of the atmosphere. But physicists now warn that we need to rethink this assumption. Increases in the amount of CO2 are now “manifest throughout the entire perceptible atmosphere,” says Martin Mlynczak, an atmospheric physicist at the NASA Langley Research Center in Hampton, Virginia. They are “driving dramatic changes [that] scientists are just now beginning to grasp.” Those changes in the wild blue yonder far above our heads could feed back to change our world below.

The story of changing temperatures in the atmosphere at all levels is largely the story of CO2. We know all too well that our emissions of more than 40 billion tons of the gas annually are warming the troposphere. This happens because the gas absorbs and re-emits solar radiation, heating other molecules in the dense air and raising temperatures overall.

But the gas does not all stay in the troposphere. It also spreads upward through the entire atmosphere. We now know that the rate of increase in its concentration at the top of the atmosphere is as great as at the bottom. But its effect on temperature aloft is very different. In the thinner air aloft, most of the heat re-emitted by the CO2 does not bump into other molecules. It escapes to space. Combined with the greater trapping of heat at lower levels, the result is a rapid cooling of the surrounding atmosphere.

The cooling of the upper air also causes it to contract, which concerns NASA. The sky is falling — literally.

Satellite data have recently revealed that between 2002 and 2019, the mesosphere and lower thermosphere cooled by 3.1 degrees F (1.7 degrees C ). Mlynczak estimates that the doubling of CO2 levels thought likely by later this century will cause a cooling in these zones of around 13.5 degrees F (7.5 degrees C), which is between two and three times faster than the average warming expected at ground level.

Early climate modelers predicted back in the 1960s that this combination of tropospheric warming and strong cooling higher up was the likely effect of increasing CO2 in the air. But its recent detailed confirmation by satellite measurements greatly enhances our confidence in the influence of CO2 on atmospheric temperatures, says Santer, who has been modeling climate change for 30 years.

This month, he used new data on cooling in the middle and upper stratosphere to recalculate the strength of the statistical “signal” of the human fingerprint in climate change. He found that it was greatly strengthened, in particular because of the additional benefit provided by the lower level of background “noise” in the upper atmosphere from natural temperature variability. Santer found that the signal-to noise ratio for human influence grew fivefold, providing “incontrovertible evidence of human effects of the thermal structure of the Earth’s atmosphere.” We are “fundamentally changing” that thermal structure, he says. “These results make me very worried.”

A view of the space shuttle Endeavor showing several layers of the atmosphere — the mesosphere (blue), the stratosphere (white), and the troposphere (orange). NASA

Much of the research analyzing changes aloft has been done by scientists employed by NASA. The space agency has the satellites to measure what is happening, but it also has a particular interest in the implications for the safety of the satellites themselves.

This interest arises because the cooling of the upper air also causes it to contract. The sky is falling — literally.

The depth of the stratosphere has diminished by about 1 percent, or 1,300 feet, since 1980, according to an analysis of NASA data by Petr Pisoft, an atmospheric physicist at Charles University in Prague. Above the stratosphere, Mlynczak found that the mesosphere and lower thermosphere contracted by almost 4,400 feet between 2002 and 2019. Part of this shrinking was due to a short-term decline in solar activity that has since ended, but 1,120 feet of it was due to cooling caused by the extra CO2, he calculates.

This contraction means the upper atmosphere is becoming less dense, which in turn reduces drag on satellites and other objects in low orbit — by around a third by 2070, calculates Ingrid Cnossen, a research fellow at the British Antarctic Survey.

On the face of it, this is good news for satellite operators. Their payloads should stay operational for longer before falling back to Earth. But the problem is the other objects that share these altitudes. The growing amount of space junk — bits of equipment of various sorts left behind in orbit — are also sticking around longer, increasing the risk of collisions with currently operational satellites.

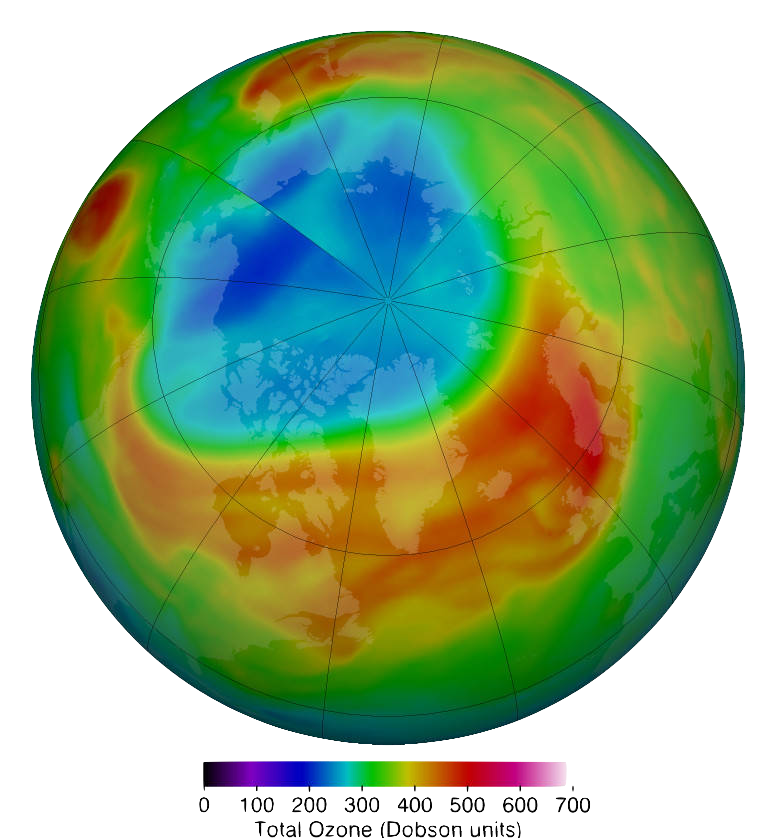

In 2020, the Arctic had its first full-blown ozone hole, with more than half the ozone layer lost in places.

More than 5000 active and defunct satellites, including the International Space Station, are in orbit at these altitudes, accompanied by more than 30,000 known items of debris more than four inches in diameter. The risks of collision, says Cnossen, will grow ever greater as the cooling and contraction gathers pace.

This may be bad for business at space agencies, but how will the changes aloft affect our world below?

One big concern is the already fragile state of the ozone layer in the lower stratosphere, which protects us from harmful solar radiation that causes skin cancers. For much of the 20th century, the ozone layer thinned under assault from industrial emissions of ozone-eating chemicals such as chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs). Outright ozone holes formed each spring over Antarctica.

The 1987 Montreal Protocol aimed to heal the annual holes by eliminating those emissions. But it is now clear that another factor is undermining this effort: stratospheric cooling.

Ozone destruction operates in overdrive in polar stratospheric clouds, which only form at very low temperatures, particularly over polar regions in winter. But the cooler stratosphere has meant more occasions when such clouds can form. While the ozone layer over the Antarctic is slowly reforming as CFCs disappear, the Arctic is proving different, says Peter von der Gathen of the Alfred Wegener Institute for Polar and Marine Research in Potsdam, Germany. In the Arctic, the cooling is worsening ozone loss. Von der Gathen says the reason for this difference is not clear.

Map showing ozone hole over the Arctic in March 2020. NASA

In the spring of 2020, the Arctic had its first full-blown ozone hole with more than half the ozone layer lost in places, which von der Gathen blames on rising CO2 concentrations. It could be the first of many. In a recent paper in Nature Communications, he warned that the continued cooling means current expectations that the ozone layer should be fully healed by mid-century are almost certainly overly optimistic. On current trends, he said, “conditions favorable for large seasonal loss of Arctic column ozone could persist or even worsen until the end of this century … much longer than is commonly appreciated.”

This is made more concerning because, while the regions beneath previous Antarctic holes have been largely devoid of people, the regions beneath future Arctic ozone holes are potentially some of the more densely populated on the planet, including Central and Western Europe. If we thought the thinning ozone layer was a 20th century worry, we may have to think again.

Chemistry is not the only issue. Atmospheric physicists are also growing concerned that cooling could change air movements aloft in ways that impinge on weather and climate at ground level. One of the most turbulent of these phenomena is known as sudden stratospheric warming. Westerly winds in the stratosphere periodically reverse, resulting in big temperatures swings during which parts of the stratosphere can warm by as much as 90 degrees F (50 degrees C) in a couple of days.

This is typically accompanied by a rapid sinking of air that pushes onto the Atlantic jet stream at the top of the troposphere. The jet stream, which drives weather systems widely across the Northern Hemisphere, begins to snake. This disturbance can cause a variety of extreme weather, from persistent intense rains to summer droughts and “blocking highs” that can cause weeks of intense cold winter weather from eastern North America to Europe and parts of Asia.

This much is already known. In the past 20 years, weather forecasters have included such stratospheric influences in their models. This has significantly improved the accuracy of their long-range forecasts, according to the Met Office, a U.K. government forecasting agency.

“If we don’t get our models right about what is happening up there, we could get things wrong down below.”

The question now being asked is how the extra CO2 and overall stratospheric cooling will influence the frequency and intensity of these sudden warming events. Mark Baldwin, a climate scientist at the University of Exeter in England, who has studied the phenomenon, says most models agree that sudden stratospheric warming is indeed sensitive to more CO2. But while some models predict many more sudden warming events, others suggest fewer. If we knew more, Baldwin says, it would “lead to improved confidence in both long-term weather forecasts and climate change projections.”

It is becoming ever clearer that, as Gary Thomas, an atmospheric physicist at the University of Colorado Boulder, puts it, “If we don’t get our models right about what is happening up there, we could get things wrong down below.” But improving models of how the upper atmosphere works — and verifying their accuracy — requires good up-to-date data on real conditions aloft. And the supply of that data is set to dry up, Mlynczak warns.

Most of the satellites that have supplied information from the upper atmosphere over the past three decades — delivering his and others’ forecasts of cooling and contraction — are reaching the ends of their lives. Of six NASA satellites on the case, one failed in December, another was decommissioned in March, and three more are set to shut down soon. “There is as yet no new mission planned or in development,” he says.

Mlynczak is hoping to reboot interest in monitoring with a special session that he is organizing at the American Geophysical Union this fall to discuss the upper atmosphere as “the next frontier in climate change.” Without continued monitoring, the fear is we could soon be returning to the days of the ignorosphere.