Two shoebox-sized satellites, each weighing less than six pounds, are orbiting Earth, flying high above places like the Greenland Ice Sheet to collect valuable data about the Arctic and Antarctic. Their unique vantage point and ability to collect global data over the course of almost a year will provide scientists with information about our changing climate that will help inform and improve climate modeling.

The two CubeSats were launched into space in late May and early June on Rocket Lab’s Electron rocket, which lifted off from New Zealand. Over the next year, these two tiny satellites will collect data to help improve climate modeling, which is especially important in the Arctic since the region is warming almost four times as fast as the rest of the planet.

When people hear NASA and space programs, many think of astronauts on the International Space Station, or sending rovers out to Mars, or even searching for extraterrestrial life and exploring galaxies far away. But NASA also frequently turns the scientific lens on Earth, with an array of projects to learn about climate change using satellites, instruments onboard the International Space Station, airplanes, and even ships, balloons, and other research platforms.

The PREFIRE (Polar Radiant Energy in the Far-InfraRed Experiment) mission will help scientists learn about heat exchange in polar regions, collecting data about how much heat Earth absorbs and emits. The difference between heat energy being absorbed and emitted shapes climate, and this mission will unlock the secrets of climate in the Arctic and fill knowledge gaps about Earth’s energy budget since much of this thermal infrared radiation has not been systematically measured before.

Earth’s tropical regions absorb heat from the Sun, and then this solar energy is transferred to the polar regions by weather and ocean currents. Once it reaches the poles, some of this heat is emitted back into space. Many factors influence these processes and how much heat is emitted at the poles, including water vapor in the atmosphere, as well as clouds and their characteristics. Much of the heat being radiated back into space is in far-infrared wavelengths, which can be difficult to measure, and this project will help fill knowledge gaps.

“It’s very difficult to go and make measurements in either polar region,” says PREFIRE principal investigator Tristan L’Ecuyer, a professor at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. While weather stations and ship and aircraft-based projects have collected measurements in many locations, L’Ecuyer says, “There’s really no way of measuring the entire Arctic or Antarctic [from Earth]… It’s really impossible to make measurements that span the entire polar regions without doing it from space.” He also emphasizes the importance of collecting year-round measurements to learn more about seasonal variations in energy fluxes.

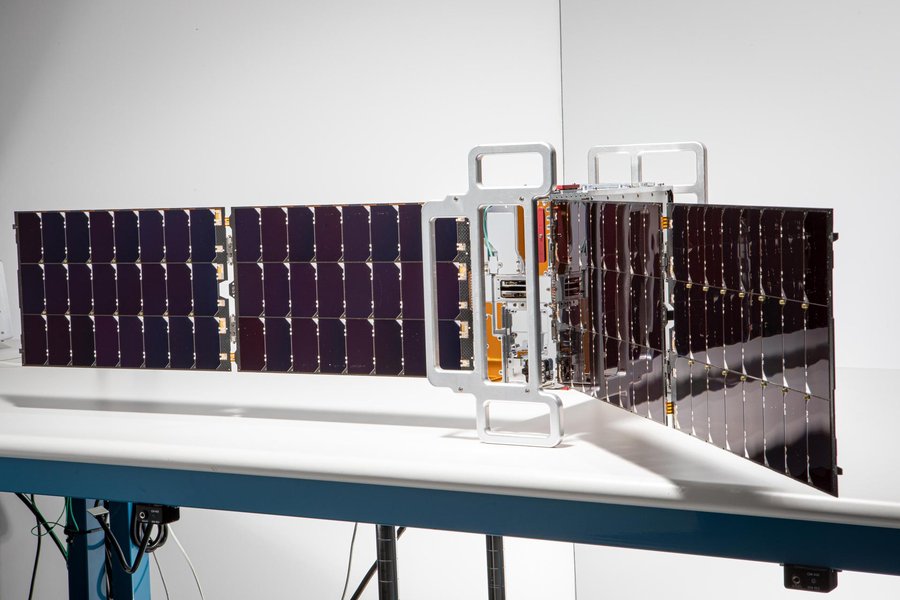

one of two shoebox-size satellites that make up NASA's Polar Radiant Energy in the Far-InfraRed Experiment (PREFIRE) mission. (Photo: NASA)

PREFIRE will obtain measurements throughout the year so scientists can learn more about how much heat the Arctic and Antarctic regions emit into space, as well as how that influences the poles, and how those factors vary seasonally. The data they collect will be used to fine-tune and improve climate and ice modeling, and to inform models that simulate processes like ice sheet melt rates. This will provide us with better ideas of what to expect regarding climate and weather in the coming years, from ice melt rates to sea level rise. Project partners include NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, the University of Wisconsin-Madison, and Blue Canyon Technologies, which constructed the CubeSats.

Having two CubeSats collecting provides not only redundancy in case one were to malfunction or acquire damage, but it also provides more data which scientists will use to learn more. The two satellites will have asynchronous near-polar orbits, collecting data about polar regions once every few hours. By collecting data so frequently, they can help track short-lived phenomena like cloud cover and changes in moisture that impact the heat energy they are studying.

“It is very important to us to be able to fly over and measure the same location,” L’Ecuyer says. Being able to make repeat measurements in a single day at a location like the top of the Greenland Ice Sheet provides data on short-term changes, like surface melting, cloud formation, and water vapor changes–things that happen on a timescale of hours rather than days. “[Having] two CubeSats that repeatedly make measurements in the same location, but several hours apart, will let us figure out not only what the heat flux at the top of the atmosphere is, but how it gets impacted by changes in the ice surface or in terms of what’s going on in the atmosphere.”

Rocket Lab’s Electron rocket is vertical on the pad Saturday, May 25, 2024, at Launch Complex 1 in Mahia, New Zealand. (Photo: NASA)

After launch, a commissioning period will allow scientists and engineers to ensure the instruments are working correctly. They will check to make sure it is oriented the correct direction, radio communications systems are working correctly, and then collect some preliminary information, such as photon counts, to make sure everything is working as it should. Once everything is confirmed to be in good order, the 10-month data collection period will begin.

PREFIRE isn’t NASA’s only project focusing on the Arctic this year. This summer, NASA’s ARCSIX (Arctic Radiation Cloud Aerosol Surface Interaction Experiment) will fly over the Arctic and study sea ice, collecting measurements.

One challenge of Arctic data collection is the brightness of clouds, ice sheets, and sea ice, which older data collection methods can sometimes struggle to differentiate between. But PREFIRE is measuring infrared wavelengths to collect measurements of cloud particle size and learn if the cloud is liquid or ice, learning about the size and phase of the particles. These factors determine if the clouds warm or cool the surface.

Technicians process NASA’s PREFIRE (Polar Radiant Energy in the Far-InfraRed Experiment) ahead of integration with a Rocket Lab Electron rocket on Thursday, May 2, 2024, at the company’s facility in New Zealand. (Photo: NASA)

These projects illustrate NASA’s key role in climate change research, with its first observations of Earth dating back to 1960 when the initial TIROS weather satellite was launched. Then in the 1980s, NASA set out to develop an Earth-observing system to learn more about the “global change.” By 2007, NASA had 17 space missions that were collecting data about climate, from aerosols and ozone in the atmosphere, to data on ice sheets and sea level rise.

While some projects involve planes or measurements taken near the Earth, space provides an excellent vantage point to get a good view of what’s happening on Earth, particularly the poles.

“In the polar regions, it’s very difficult to measure things from the ground,” L’Ecuyer says. “And even when we’ve had aircraft, it’s actually very difficult to fly aircraft—there are not a lot of airports In the Arctic.”

That’s where NASA comes in with its unique vantage point.

“NASA actually does a lot of work to try to improve our understanding of climate,” L’Ecuyer says. “NASA is able to measure things around the entire globe. It’s really the only way that we get information from all the very remote areas of the globe.”