300 Pounds. That was the weight of my team’s checked-in baggage at the Nain airport. We were heading back home to Calgary and more than half of that weight was our precious samples that we had collected and our experiments that we had set up onboard Arctic Research Foundation ship, R/V William Kennedy, sailing from St. Anthony to Nain. Our journey started two weeks earlier, when my team of researchers from the University of Calgary and I left to study the unseen in the Labrador Sea. I am a microbiologist. I study life that although abundant everywhere around us, is not visible to the naked eye.

The team's luggage when returning from the the Labrador Sea (Photo: Srijak Bhatnagar)

What do they look like? What do they do? What do they eat? What connects us to them? Why do they matter to us? These are some of the questions I have been asked. They come in all shapes and size, albeit small. They eat different things. They are part of the global cycles that connects us all. They carry out many important processes that make them indispensable to marine life and to everyone on the land that depends on the ocean. There are different types of microbes, in different proportions, in different parts of the oceans, across the planet. Thus, microbial life is an easy-to-measure indicator of health of an ocean or any other ecosystem.

"Given the turbulent nature of Labrador Sea and it’s economic and ecological importance, it is very important to understand the microbial biodegradation of oil in it."

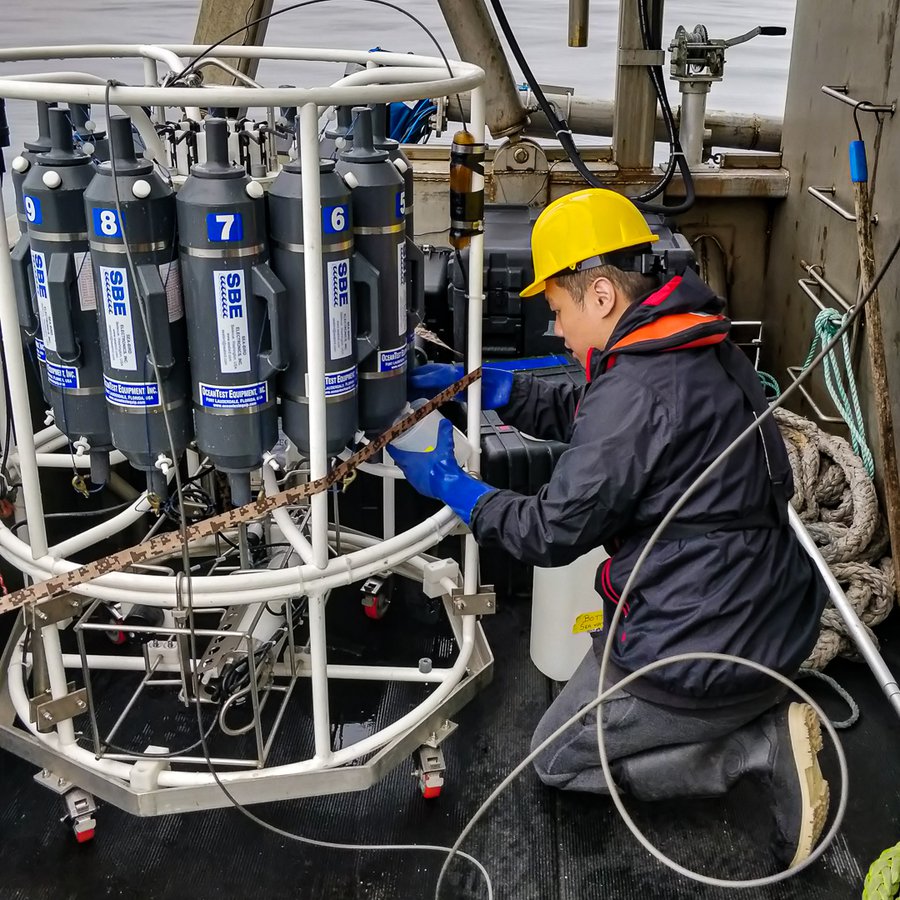

Calvin Kong collecting water samples with a rosette. (Photo: Srijak Bhatnagar)

As part of a Genome Canada funded project, GENICE, I along with a group of researchers across Canada, are mapping the microbial life of Canada’s Arctic and Sub-arctic waters. We are identifying the different microbes that live in the sea and its depths – all the way down to sea floor. And this trip to the Labrador Sea is part of that puzzle.

The R/V William Kennedy

But what brought me to Labrador Sea is much more than that puzzle. The Labrador Sea is part an active oil exploration and production zone in Atlantic Canada. Which makes it vulnerable to oil spills. In fact, there have been an oil spill this year and the last year in the Labrador Sea/North Atlantic Ocean. Depending upon the country’s regulation and the region where oil spill happens, the response to an oil spill varies. These responses usually include controlling the spread of oil, sucking up the oil, burning it, and using dispersant, among other things. These processes do not remove all of the spilled oil from the environment. So, no matter what the response is, a sizable fraction of oil is cleaned up by microbes. Yes, microbes!

Calvin Kong and Brielle Hrymoc working aboard the R/V William Kennedy. (Photo: Srijak Bhatnagar)

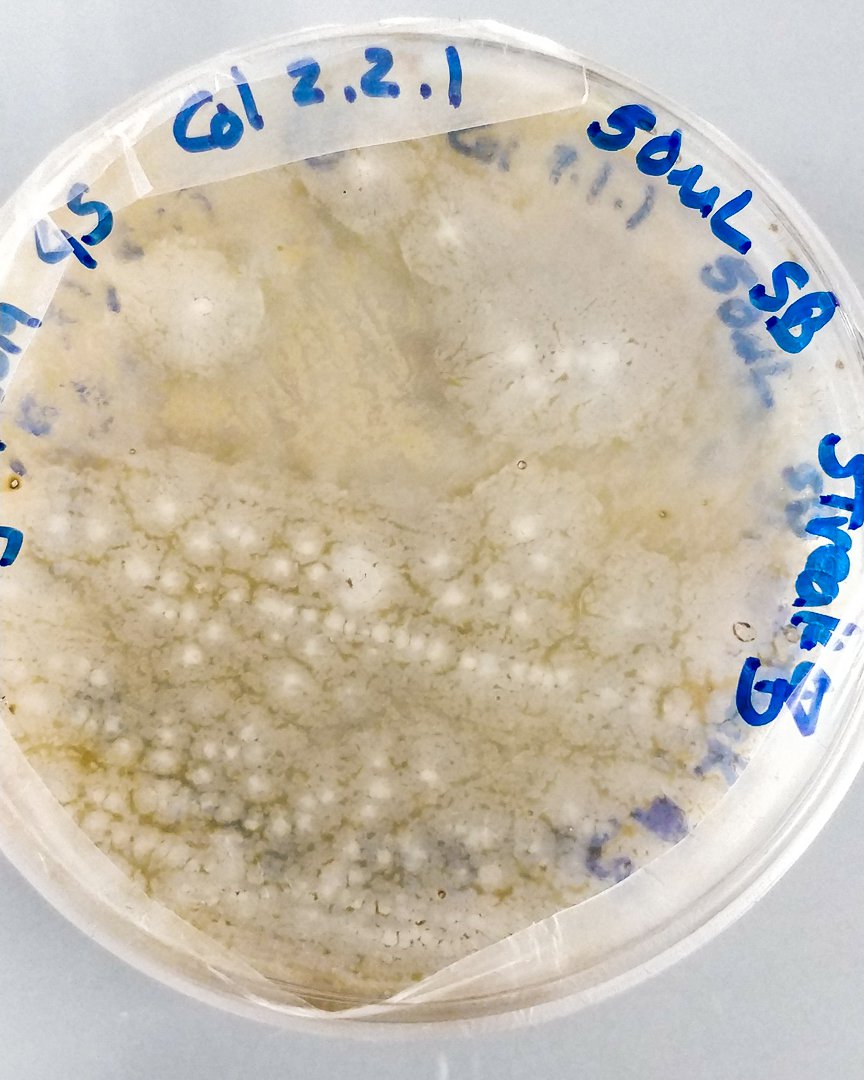

There are microbes, called hydrocarbon degrading bacteria, for which the oil is a food or they breakdown oil to be able to survive. The hydrocarbon degrading bacteria are present in our oceans. Their role becomes more important, when the oil spill is not contained or cleaned up completely. This has happened more than once offshore Newfoundland and Labrador. In 2018, the largest oil spill in the history of Newfoundland (about 250,000 liters) was not completely cleaned up because of a storm. This year, twelve thousand liters of crude oil was spilled in the Labrador Sea and only about 10% was cleaned up. The responsibility of this clean up falls on the microbes - Our allies in the ocean and the agents of biodegradation. For example, it is estimated that between 10 to 25% of oil in Deep Water Horizon spill was consumed by microbes.

Oil degradation bacterial colnies. The white areas show where crude oil was eaten away. (Photo: Srijak Bhatnagar)

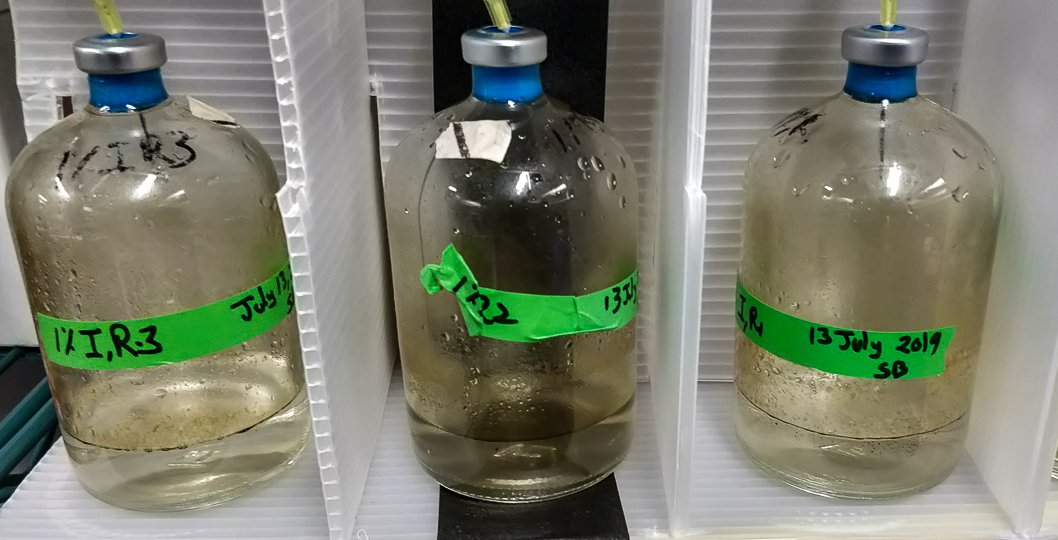

Given the turbulent nature of Labrador Sea and it’s economic and ecological importance, it is very important to understand the microbial biodegradation of oil in it. This is what brought me to the Labrador Sea, to find these microbial allies in this sea water that eat oil. We set up experiments on board M/V William Kennedy, where we simulated an oil spill in a bottle using sea water from the surface of the ocean. Then we studied what happened to the microbes in the seawater, which one survived, which one grew up using the crude oil. While this research is ongoing, we have been able to see the effects of oil on the population of the sea water microbes and identify which of these microbes from the Labrador Sea are able to eat oil. This knowledge will help us harness the power of microbes to clean up our messes and possibly help us inform to make region specific oil spill cleanup strategies. Because our oceans are invaluable.