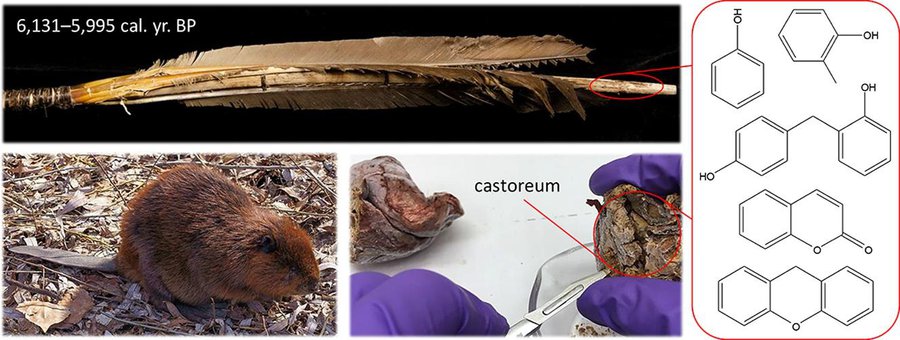

Researchers were in for a smelly surprise when they analyzed an ancient throwing dart in Yukon. Pulled from the alpine ice in the traditional territories of Kwanlin Dun and Carcross/Tagish First Nations, the artifact had an unexpected and puzzling component in its design – beaver castoreum, a sticky, reddish substance secreted by beavers.

Kate Helwig and Jennifer Poulin at the Canadian Conservation Institute—a special agency of the federal Department of Canadian Heritage dedicated to the research and preservation of Canadian cultural artifacts—headed the study.

The discovery first came about when long—time Yukon Museums Conservator and Whitehorse—resident Valery Monahan, who co—authoured the study, noticed an odd orangish—residue binding the sinew and wood of the two—meter long dart. She didn’t really think it was very noteworthy at first, she said, especially because organisms “can grow funky things like bright colours in moist environments,” and for all she knew, it could have been the remains of “some slime stuff.”

“I've seen lots of orangey stuff on objects (like these in the past) and it has universally been one of two things before this: it's either been an ochre based paint of some kind, or it's been a mixture of red ochre and spruce resin that is a form of adhesive used to stick the stone components to the other components,” says Mohanan.

“When we sent the samples off... to my colleagues in Ottawa who have been doing this analysis for years and I said, ‘Okay...looks like more kind of ochre paint on the back end… but oh, by the way, there's also this kind of weird orange chalky stuff that seems to look like it's sort of between a couple of joints on the dart… I don’t know what it is.”

Helwig and Poulin used gas chromatography—a form of chemical analysis to analyze the sample. What they found surprised —and delighted—the researchers.

“This is one of their favourite projects… (Poulin) was literally jumping up and down with excitement saying ‘oh my god, it’s castoreum!’”

Castoreum, which is used in perfumes, the manufacturing of artificial vanilla, and even to flavour a kind of Swedish schnapps called Bäverhojt (Beaver Shout), is a sticky, brightly coloured substance secreted by beavers from glands, called castor sacs, near the anus. Beavers – the second largest rodents in the world – use the stuff to tell relatives apart and mark their territory; trappers traditionally used castoreum on their traps, says Monahan, because the odour would draw beavers out in search of potential rivals.

The substance is also notoriously foul-smelling, and in order to confirm that what they were looking at really was castoreum, the team had to analyze a fresh sample.

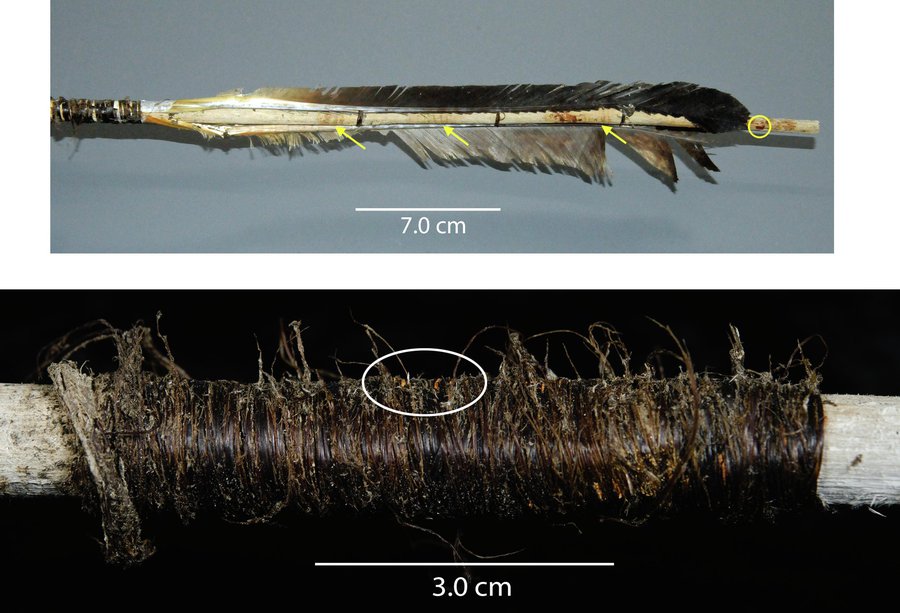

Top: Proximal end of the dart with red residue. The residue includes three sets of faint lines (marked with arrows). There are also thicker, less uniform accumulations of residue near the proximal tip and in a few other zones within the fletching area. The approximate location of sample 1, near the proximal tip, is circled. Bottom: Proximal scarf joint with sinew wrapping. Orange-red residue is visible at gaps between the sinew strands. The circled area shows the approximate location of sample 2. (Photographs: Yukon Government)

“It’s funny,” says Monahan, who is in charge of residue analysis on the Yukon end and so handled the sample, which was acquired through the Yukon Department of Environment. “It smells really gross, but it also smells really good. It has this really strong animal musk, but it also has this really strong cedar and wood and vanilla smell.”

“Beavers are one of the few animals in the world that can directly metabolize cellulose as food... and that’s why their castoreum smells... because they’re repurposing the chemicals in the cellulose for themselves.”

Why exactly the maker used castoreum on the dart and how common the practice was is a bit of a mystery, says Monahan — it may have been some kind of adhesive, or the reddish colour may have had cultural or spiritual significance.

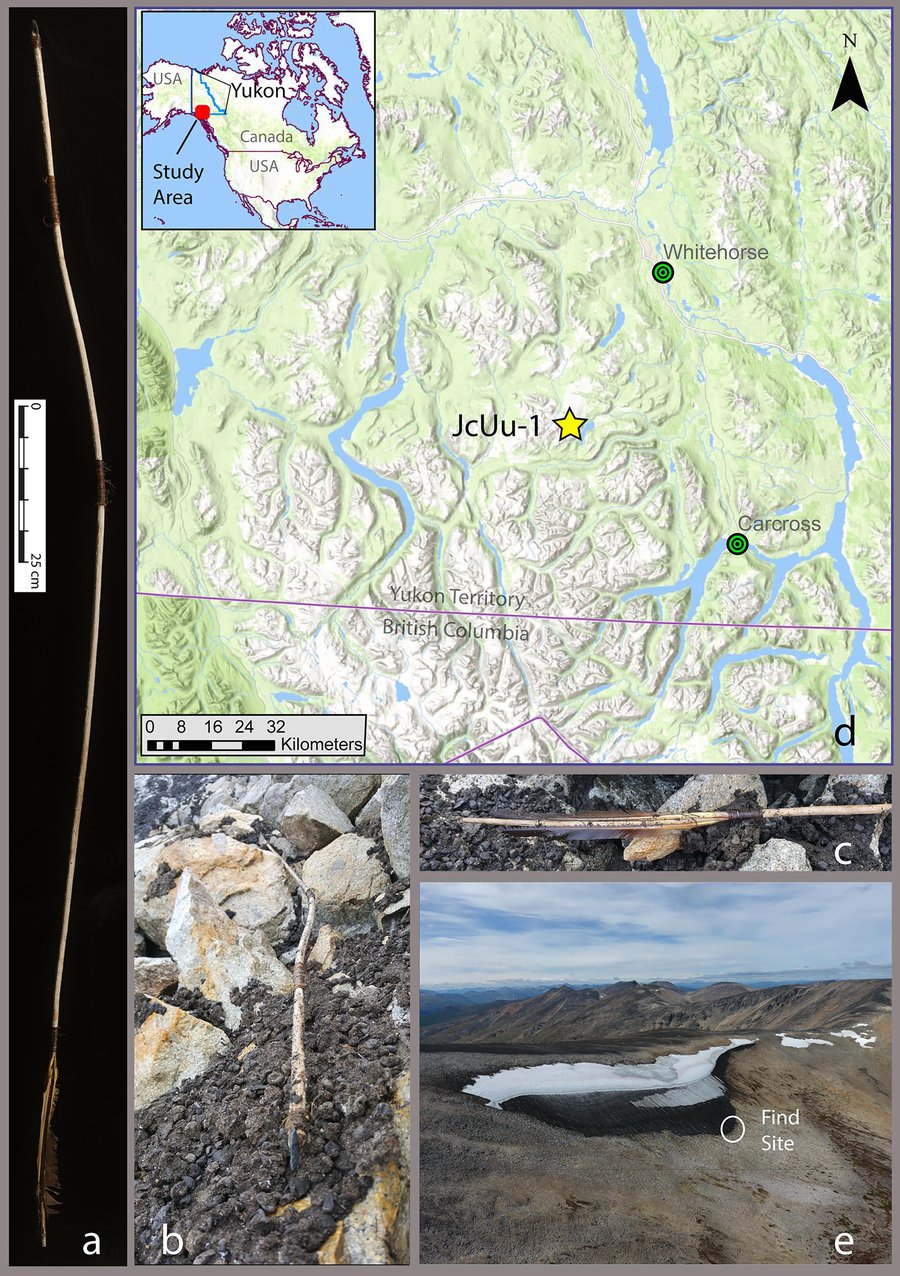

Monahan says finding the substance on such an ancient tool is “cool for a couple of reasons,” one of which is that the team believes this is the first time a castoreum has been identified in an ancient archeological context. Another is simply the dart itself, which is part of a larger Yukon collection and research initiative, the Yukon Ice Patch Research Project, a collaboration between Carcross/Tagish First Nation, Champagne and Aishihik First Nations, Kluane First Nation, Kwanlin Dün First Nation, Ta’an Kwäch’än Council, Teslin Tlingit Council and the Government of Yukon.

The first artifacts in this collection which were recovered in 1997, many are thousands of years old and “incredibly well preserved,” says Monahan, who has been working with the collection for more than 20 years.

The throwing dart, which is also sometimes called an atlatl, is a long, spear—like weapon, which would be thrown by placing it into a handled launcher which worked similarly to the popular ball-throwing dog toy, the Chuck-it, allowing the user to throw the projectile with substantially improved distance, power, speed and accuracy. It would have been used in hunting game, such as a caribou, and was the preferred hunting weapon for Yukon First Nations before 7 AD. It was fully replaced by the bow and arrow around 847 AD.

Photographs of the find location and artifact JcUu-1:33, a complete throwing dart recovered in 2018 from ice patch site JcUu-1: a) composite photograph of the dart, b) dart in its discovery location, showing the distal end, c) dart in its discovery location showing the proximal end, d) map with location of the ice patch site JcUu-1, near Alligator Lake, southern Yukon, in the overlapping traditional territories of the Carcross/Tagish First Nation and the Kwanlin Dün First Nation, e) view of the ice patch JcUu-1 from the west with approximate find location marked. (Photographs and map: Yukon Government.)

First Nation researchers and elders have identified and confirmed a whole series of hunting trails and blinds in the ice patches where the dart was recovered, some of which go back 9,000 years, says Monahan.

“Our ancestors were connected to the land, the water, and the animals in our Traditional Territories. They understood how to use the things around them to design complex and ingenious tools, like the atlatl. Shä̀w níthän (thank you) to all of the people who worked together to bring this ancient technology into the light so our people can continue to learn from the knowledge of our ancestors,” Kwanlin Dün First Nation Chief Doris Bill said of the discovery via press release.

“Our lands hold many secrets and insights into the past,” Carcross/Tagish First Nation Haa Sha du Hen (Chief) Lynda Dickson added. “Unearthing and studying these findings is valuable not just from a scientific and historic perspective, but culturally. Walking hand in hand with the land, water and wildlife is the history of our people. Their resourcefulness and ingenuity continue to impress and teach us. Gunalchéesh (thank you) to the people helping keep us connected to our ancestors.”

Although discovering the castoreum on the dart is a valuable and fascinating archeological find, there is a dark side to it, says Monahan.

“The sad thing is that we are finding these things in this ancient, ancient snow and ice that’s been stable for years because it’s melting,” she says. “The fact that we are finding this material now is definitely related to climate change.”