Why is it that some communities manage to deal with change while others struggle? Despite systematic oppression over the past sixty years, the Inuit community of Cape Dorset, Nunavut, Canada has transformed themselves from nomadic hunters to internationally renowned artists within six decades. However, in other communities, such as the reindeer herders of Teriberka, Russia have had their traditional livelihoods suppressed by government push for oil and gas development in the district.

These stories, along with several others describing both success and hardship, are part of the Arctic Resilience Report (ARR), one of the most comprehensive assessments of rapid social and ecological changes facing the Arctic. Published in 2016, it was the first project to assess resilience over a large international region. The report looks at the Arctic as a social-ecological system; a perspective where humans and nature are embedded within each other; and aims to understand system dynamics in the Arctic through this lens.

It examines how human activity and climate change has affected the people and place, and uses case studies from the region to explore what we can do about it. Miriam Huitric, researcher at Stockholm Resilience Centre at Stockholm University and chapter lead author elaborates: "Rising temperatures are driving rapid change in the Arctic, in addition to a range of other drivers that are also driving change, so understanding what supports and erodes resilience is crucially important for both people of the Arctic and its ecosystems.”

Thick surface meltwater covers the sea ice near Uummannaq, Greenland, where the local Inuit population relies heavily on ice coverage for fishing and travelling with dog-sleds. (Lawrence Hislop/Grid Arendal Photo Library (http://bit.ly/2ciBBD9)

The bigger picture

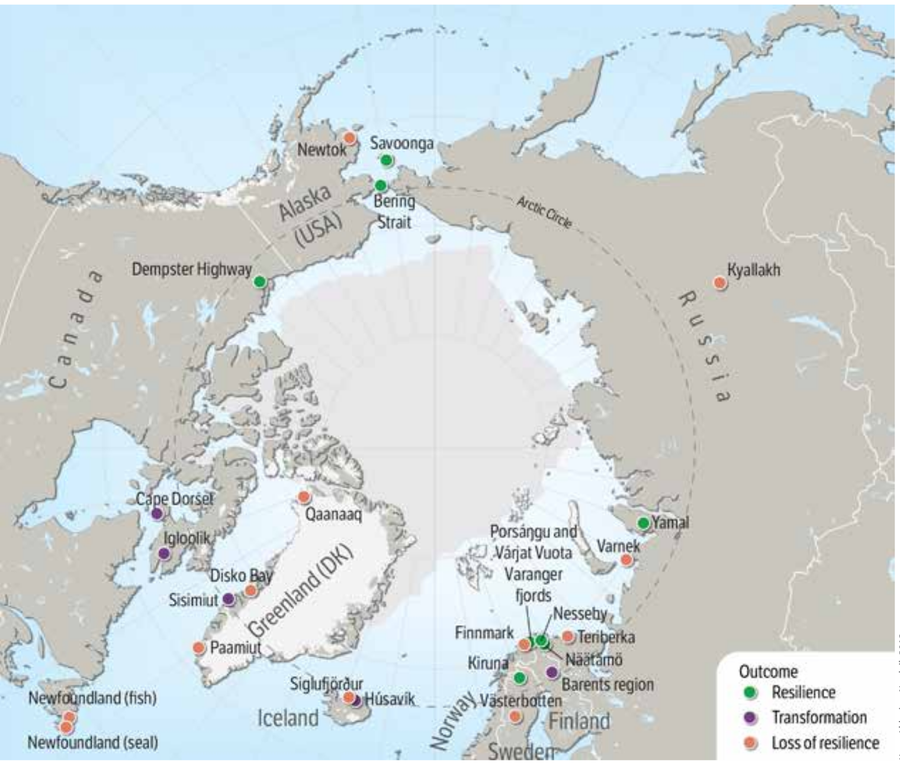

The ARR explores resilience in 25 Arctic cases. Resilience in this report is defined as the capacity to navigate change by buffering, adapting, or transforming to stress and shocks.

By examining the cases collectively the authors were able to identify several behavioural patterns that could help build resilience amid rapid change:

- Arctic peoples have often shown a high capacity to adapt and self-organization is important for their ability to change.

- National policies are becoming increasingly important as mineral and resource extraction are more sought after. Policies play a defining role in how local communities are affected by these activities.

- The Arctic Council is an important meeting place for sharing knowledge about the Arctic. However, there are gaps in understanding social-ecological behaviour in the region.

- Other stakeholders could be increasingly useful for supporting local and Indigenous knowledge in the region, particularly when it comes to local adaptation building for local communities.

The authors emphasize that the ability of local communities to organize their own responses was a key ingredient when it comes to fostering resilience to rapid change in the Arctic. The loss or suppression of this capacity was present in all the cases in which resilience was lost. Nurturing social and ecological diversity as well as practices that enabled people to learn

from change and surprise were also important when it came to communities being able to transform, such as the Inuit population of Cape Dorset, Canada.

Responding to Arctic change: a selection of 25 case studies from across the Arctic were analysed for the report. The cases illustrate both loss of resilience and resilience, including instances of transformational change.

“We hope the insights presented in the Artic Resilience Report will help Arctic nations to better understand and deal with the changes taking place in the region, and strengthen Arctic people’s capacity to navigate the rapid, turbulent and often unexpected changes they face in the 21st century,”

Miriam Huitric

Regime shifts: A new Arctic

Melting sea ice and shrinking glaciers illustrate just how much the Arctic landscape is changing. The ARR also analyzed what bio-physical arctic tipping points, also known as regime shifts, could exist. A regime shift is a large and persistent change that affects the structure of a social-ecological system. It can be thought of as a loss of a resilience in one system state, before shifting into something new. While it may seem like it would be obvious when a regime shift is about to occur, it is not. In the real world, no system is in isolation, and regime shifts occur both due to events, such as fires or exceptionally warm weather, pushing systems over ‘tipping points’ as well as slower changes that shift biophysical processes that alter the conditions under which tipping points can occur.

Juan Carlos Rocha, a Stockholm Resilience Centre researcher and co-lead author of the ARR chapter on regime shifts, explains, “Understanding of regime shifts is important, because along with their potential impacts on economies, societies and human well-being, they are often difficult to anticipate and costly or impossible to reverse.”

For example, in the Arctic there has been a shift from coniferous forests to deciduous forests. It has been driven by climate change, but the newly established deciduous trees are also playing a role. These trees change the entire ecosystem, regional albedo, as well as make the local climate warmer and more humid, promoting the growth of more deciduous trees. Changes in forest composition can also increase the frequency of fires, shifting the role of forest from carbon storage to carbon emitters, further reinforcing global warming. This is called cascading regime shifts and the Arctic is a hotspot for such effects. What happens in the Arctic does not stay there, but rather threatens to impact regime shifts outside the Arctic. Recent research links changes in the Arctic to fires in California and heat waves & storms in across the Northern Hemisphere.

The majority of the 19 regime shifts identified in the ARR occur in marine and polar systems. 12 of the regime shifts were irreversible within the next 100 years, the authors found. This means that within our lifetimes, we will never be able to reverse some of the changes already set in.

Co-editor of the report, Garry Peterson, professor at Stockholm Resilience Centre, Stockholm University explains, “The impact of Arctic regime shifts on Arctic culture, social memory and sense of place seems to be large and set to substantially increase. The cumulative impacts of multiple regime shifts are likely to severely disrupt the Arctic landscape and completely reshape how people live and move around the Arctic.”

(Photo: Mark Tozer)

The way forward

The 217-page report provides important insights on regime shifts, adaptability, and ways of navigating transformation. The theoretical orientation of resilience thinking is especially important in the Arctic, where rapid change is raising concerns about ecosystem health and human well-being. While the application of resilience theory is underdeveloped, there are insights and examples for application in the North. While resilience theory is well

established, putting its principles into practice is neither simple nor straightforward. In the final chapter, the authors highlight six questions to ask that help evaluate strategies for building resilience:

- Are the goals clear?

- Are multiple kinds of knowledge being integrated?

- Are place-based community partnerships being supported?

- Are linkages being made across scales?

- Is social learning being facilitated?

- Is culture taken into account?

These questions are particularly important for decision-makers, and can be used as a starting point for applying resilience practice. While more monitoring and research are needed in the Arctic, these activities must be linked with appropriate policies and actions. Local communities and indigenous people can provide knowledge and capacity to help Arctic people and ecosystems to respond to a rapidly changing region, and such activities can also provide opportunities for the people to determine and shape their own development.

Putting resilience thinking into practice is a “multi-scale enterprise” that requires a wide range of connections and collaborations. Such activities must address historical injustices, power inequality, as well as variation in people’s local-level needs, and need to combine both bottom-up and top-down approaches.

The hope is that this report will act as a guide when it comes building resilience above the 66th parallel north.

“We hope the insights presented in the Artic Resilience Report will help Arctic nations to better understand and deal with the changes taking place in the region, and strengthen Arctic people’s capacity to navigate the rapid, turbulent and often unexpected changes they face in the 21st century,” says Miriam Huitric.