umans are naturally risk-averse. We try to avoid disaster zones, and don’t like to fly when there appear to be mechanical problems or heavy fog. However, often information about risk is incomplete, and sometimes we don’t even know the risks we’re taking until after the event. Even for thrill-seekers, identifying and managing risk is a prudent approach.

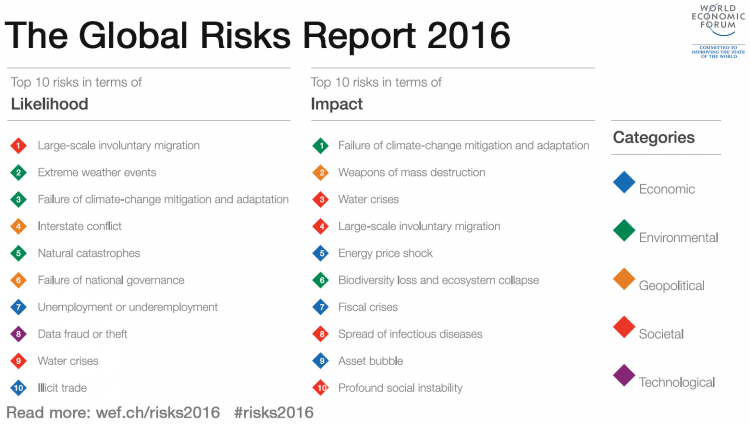

While there isn’t an official “barometer” of global risk, understanding global risk is big business, with companies such as Allianz publishing an annual global business outlook. Others look to global financial performance measures – such as the trends in the FTSE 500 or Dow Jones Index – to predict global economic resilience or vulnerability.But financial performance isn’t the only barometer of global economic risk. Indeed, the Forum’s annual Global Risks Report draws on the insights of 750 worldwide experts to identify the likelihood and perceived impact of economic, environmental, geopolitical, societal and technological risks. In 2016, for the first time ever, these experts ranked “failure of climate change mitigation and adaptation” as the looming global risk with the biggest potential impact – ahead of migration and terrorism.

The latest Global Risks Report shows that experts believe our planet is significantly changing – environmentally, socially and industrially. Climate change spans these domains, and it is reassuring that in 2015 leaders of all countries acknowledge its serious potential impact on life and our economies by adopting the first-ever universal and legally binding global climate deal, the Paris Climate Agreement.

So the question is, what barometers are there to help us monitor this kind of planetary risk? CO2 emissions parts per million is obviously a barometer to watch, but it remains invisible to the human eye, so for some seems like an abstract number on a chart.

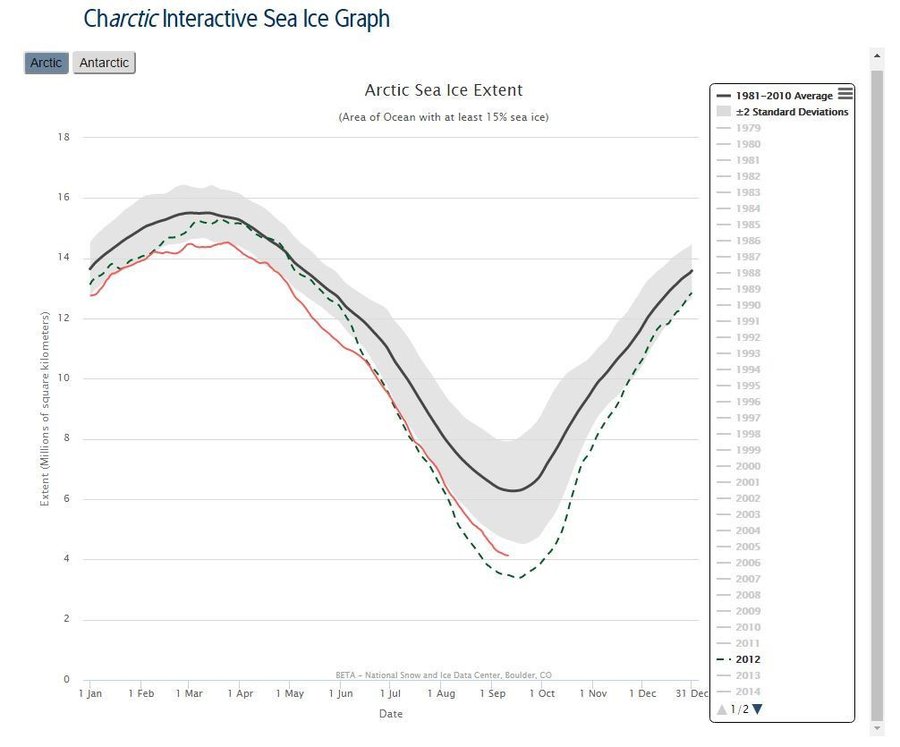

In contrast, the Arctic sea ice is a simple and visible barometer of climate change, one that clearly shows how our planet is altering because of a warmer climate. In fact, sea ice is a near perfect indicator, as it is very sensitive to changes to the temperature of ocean and atmosphere. In simple terms, the colder the climate, the more sea ice we have, and the opposite is true when the climate is warmer. Unfortunately, the Arctic has warmed at more than twice the global average, and as a result we have melted more than half the summer sea ice in the Arctic since the late 1970s.

Each summer, scientists carefully watch the Arctic ice melt season, from satellites, ships, aircraft as well as on the sea ice itself. The profoundness of the decline of Arctic summer (and winter) sea ice is hard to deny.

Image: National Snow and Ice Data Center

Rapid changes happening in the Arctic are a warning sign that our social-ecological-economic system is out of whack. Significant change in the Arctic is a particularly large global risk because the Arctic has a fundamental impact on our planetary operating system – what happens in the Arctic will affect all of us. And Arctic change comes with a heavy economic cost.

If the Arctic is a barometer of global risk, how can we improve on its calibration? There are three ways:

Communicate Arctic science to global leaders

Arctic science is incredibly impressive as a field of study. However, a key area for improvement is the way we share the implications of this science with global leaders. If the Arctic is a critical barometer of global risk, then we have to get this message out there to leaders all around the world – and not just leaders from Arctic countries. Arctic change bears significant economic and societal risk for many countries around the world, particularly those already vulnerable to climate change. Because of its role in the global climate system, Arctic change is a relevant barometer of risk for global industry sectors like agriculture, insurance, tourism and transportation.

Arctic science needs to set up regular communication channels – and that means attending events like the World Economic Forum’s Annual Meeting, to communicate trends and answer questions on global risk and opportunities for systemic and resilient transformation. An Arctic science global response Team could help steer this kind of initiative. And engaging with high-tech corporate innovators like Google and Facebook could help Arctic science enter into the mainstream.

Establish an international Arctic science superfund for global risk analysis

Currently, about 40 countries conduct scientific work in the Arctic, and almost every one of these nations works independently in terms of funding. So while polar scientists are renowned for their collaborative work across cultural divides, the international nature of this funding is almost non-existent. We need more structure to create a global systemic approach to Arctic research. The best way we can get the right knowledge is a global collaboration; an Arctic Superfund for Global Risk Analysis can help direct these efforts in a strategic way.

Breakthrough funding – the powerful role of society and private benefactors

Arctic science relies upon the ingenuity of intellectual capital from around the world. But Arctic science also needs financial resources to support current studies and to plug the gaps in our knowledge in this complex region. While many national countries actively support Arctic science, there is still a shortfall in funding requirements.

Sure, there is an opportunity for governments to up their game and increase the funding base, but we also need to go beyond the level of national interest. One way to do this is to actively encourage private benefactors to get this to a breakthrough level. If the Arctic Science Superfund is going to make a real difference, it will need to engage with groups across every sector of society, and in particular obtain strategic guidance from the world’s wealthiest people. Maybe it’s time to get entrepreneurs and business leaders out of the office and into a parka.

Gail Whiteman is Director of the Pentland Centre for Sustainability in Business and the creator of Arctic Basecamp, a group of intrepid Arctic scientists dedicated to bringing the message of global risks from Arctic change to the world’s top decision-makers.

Jeremy Wilkinson is a sea ice physicist with the British Antarctic Survey and co-organizer of Arctic Basecamp.

This article was originally published by the World Economic Forum.