Present day wolverines, which emerged during the ice age, have been declining globally despite their many adaptions to live in challenging, rugged environments.

These large land-dwelling weasels evolved to scramble up trees and climb steep, snowy mountains. Wolverines’ snowshoe-like paws, heavy frost-resistant fur and powerful muscles let them thrive in some of the coldest places on Earth. Their sharp claws and strong jaws allow them to feast on carcasses and hunt species of all sizes from ground squirrels to elk.

While wolverines have been filmed hunting caribou in Norway and observed battling black bears over food in Yellowstone, they are extremely vulnerable, rarely seen and hard to study. Wolverine numbers are declining globally due to heavy trapping and predator killing by humans as well as habitat loss, climate change and various other factors. Scientists estimate there are more than 10,000 wolverines in Canada, but population densities vary a lot and numbers are difficult to estimate.

Our 20 years of synthesized research about wolverines shows that the best ways to protect remaining wolverine populations are to reduce trapping, minimize predator control pressures and connect the large blocks of intact habitat they need to survive.

Not as resilient as you might think

Wolverines are private, generally solitary, species. They are slow to reproduce and have an average of two cubs, or kits, every two to three years.

Wolverines are slow to reproduce as they give birth to an average of two kits every two to three years. (Shutterstock)

They are naturally low in number and defend territories as large as 500-1,000 square kilometres, or sometimes more. These traits make them vulnerable to human impacts around the world.

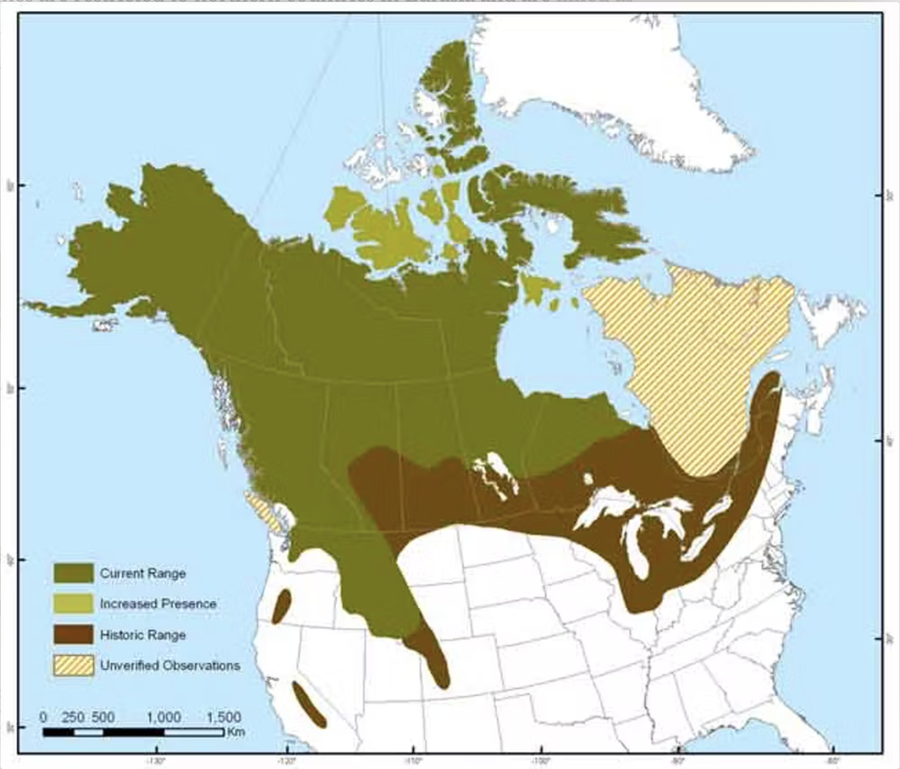

Since the Europeans colonized North America, fur trapping and landscape development shrank the wolverine range drastically. South of the wide Arctic range, wolverines can be found only in the western boreal forest and mountains. But they used to live from coast to coast and as far south as New Mexico.

Today, in the United States, only around 300 remain in the lower 48 states — mainly in the snowy strongholds and high elevations of the mountain ranges. Wolverines are restricted to northern countries in Eurasia and are killed as predators of reindeer herds in Fennoscandia.

Wolverine distribution in North America. (Environment Canada)

As tough as they are, wolverines are sometimes eaten by other big predators. As scavengers, taking food from a hungry bear or pack of wolves is a risky lifestyle. Their habitat is degraded by resource development, including forestry, oil and gas and roads. People still trap wolverines in Canada, often far too heavily. They can also be sensitive to recreation.

All this human activity makes life better for wolverines’ competitors — coyotes. Where coyotes exploit developed landscapes, they come into conflict with wolverines, and in these fights, wolverines lose.

Piled on those problems is the impact of climate change on wolverine habitat. The cold, snowy refuges that wolverines have sought south of the Arctic are now thawing. Wolverines need snow to cache food, to raise their vulnerable kits safely and to keep lowland competitors away. The one-two punch of landscape change and climate change are making matters worse for wolverines.

Building blocks for wolverine conservation

Wolverines need large, connected blocks of intact habitat to survive. The only way to protect them in the long run is to help protect and connect their fragmented blocks of habitat.

Prime wolverine habitat near Revelstoke, B.C. in summer. Wolverines need large areas of intact, connected habitat to survive. (Mirjam Barrueto/WolverineWatch.org), Author provided

Creating more protected areas and managing human activity within and next to them will help. Protecting “climate refugia” — the last bastions of cold wolverine habitat — is an important priority. Landscape planning to connect mountain refuges across busy degraded valley bottoms is sorely needed, especially in southern Canada and the United States

Work to maintain or improve ecological connectivity is happening in some places, such as from Yellowstone to Yukon and other areas in the world.

Roads and industrial development cut up major sections of prime habitat. We can fight habitat fragmentation by making better decisions about road-building, including when to decommission roads built for resource extraction and mitigating the effects of traffic on wolverines and other wildlife. Habitat protection, connectivity and restoration are critical for wolverines.

We also need transboundary co-ordination. We need to think across larger landscapes, especially regions that still support wolverines on both sides of a border — like between Canada and the United States or between Norway and Sweden.

No longer ignorant nor blissful

Globally, governments have insufficiently protected wolverines.

Sweden’s predator stewardship program is an exception and British Columbia has stopped wolverine trapping in small locales.

Otherwise, large-scale wolverine conservation has been on the back burner. In the U.S., a petition to list wolverines on the federal Endangered Species Act was thwarted. Canada lacks a federal management plan and British Columbia’s most recent wolverine plan is from 1989, while Alberta lists the species in the “data deficient” category.

A wolverine at a research station in southeastern British Columbia. We know a lot about wolverines. All we have to do is use the knowledge and act fast. (Mirjam Barrueto/WolverineWatch.org), Author provided

For years it seemed like not much was known about wolverines, and policy-makers have rested on wolverines’ mystery to excuse inaction.

The truth is, science knows a lot about wolverines. Research from around the world clearly shows what we need to do.

Wolverines may have evolved in the cold but the heat is on us to act now. We must use the research compiled over the past two decades to make the changes needed to conserve wolverines.

This article originally appeared in The Conversation