A diverse team of researchers from across Canada are filling gaps in Hudson Bay’s ecosystems. A team of scientists set sail around Southampton Island, located in the Kivalliq region of Nunavut near the entrance of Hudson Bay. Deploying rosettes from the research vessel to collect water samples, using box cores to examine sediment and sorting the contents of benthic trawls to study small organisms.

These researchers from the Southampton Island Marine Ecosystem Project (SIMEP) completed what C.J. Mundy, Chief Scientist for the University of Manitoba project, said is the ‘first ever circumnavigation of the island‘ in one cruise.

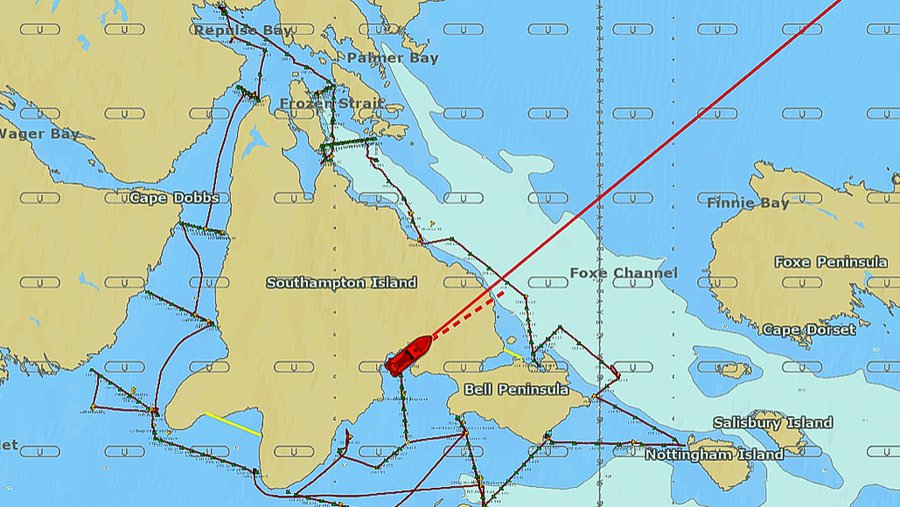

A map showing the R/V Willaim Kennedy's circumnavagation of Southampton Island.

The team of researchers were able to sample 30 sites around Southampton, collected 200 CTD tests, an instrument which measures conductivity, temperature and depth, and completed 87 dives in the area over a span of close to one month. The team was also able to collect over 300 samples of fish and invertebrates as well as observe dozens of polar bears and walruses around the island.

“We will be able from this data set to answer some very unique questions,” said Mundy. “from why are there walruses on the South end of the island to why are there mainly narwhal and bowhead [whales] on the on the North side.”

Researchers preparing a net that is dragged from the vessel collect samples of small organisms (Photo: Audrey Limoges)

The project is meant to grow the understanding of the marine ecosystem by measuring both the current and historical conditions. This, in turn, will supply communities, fisheries and government bodies with more information to guide policy and decisions with environmental factors in the area.

The team includes researchers from several universities and government departments, including the University of Manitoba, University of New Brunswick, Université Laval, Environment Canada and Department of Fisheries and Oceans.

Samples collected from a benthic trawl. (Photo: Audrey Limoges)

This is the second year the team collected samples in the field while aboard the Arctic Research Foundation’s Research Vessel William Kennedy. Unfortunately, as is common in Arctic research, last year was plagued with poor weather that confined the scientists to one side of the island.

Mundy said many areas the team was able to reach this year haven’t been sampled for several decades, if at all.

“It’s really an understudied and under sampled area, “he said. “This vessel, which is really neat and new for the Arctic… adds a new dimension that we get to explore.”

The Arctic Research Foundation's R/V William Kennedy (Photo: Audrey Limoges)

Mundy said Hudson Bay is typically seen as a dessert for biological activity, but recent data highlighted Southampton Island as a hotspot of marine life. In fact, some of the largest numbers of marine mammals and birds in the area are near the coast of the island. That, says Mundy, is what sparked his teams’ interest.

“How could a dessert be supporting such an intense amount of higher trophic levels,” said Mundy, “in an ecosystem like the Arctic you don’t expect that to happen.”

Water samples will measure how the nutrients and other physical properties including, salinity and carbon levels are dispersed throughout the water. Nets, dragged across the sea floor by the William Kennedy, collect organisms from plankton to small fish and crustaceans.

Mundy said by analyzing the primary producers and bottom of the food web it can give researchers a better idea of how much life it can in turn support.

A walrus observed near Southampton Island. (Photo: Audrey Limoges)

Audrey Limoges is a paleoceanographer with the University of New Brunswick. Her work is the key to measuring the ecosystem from years past. By collecting vertical layers of sediment from the last millennia and fossils found within them, she can date the layers to learn more about the ecosystem at that specific time period.

“We aim to reconstruct the long-term evolution of the system… in relation to climate fluctuations of the past. While collecting mud may seem trivial, it is quite challenging in northwestern Hudson Bay,” said Limoges.

The project wrapped up it’s sampling season in August 2019 and will now take the next 2 years to analyze and publish the results. The team will also return to communities in the area to share their findings.

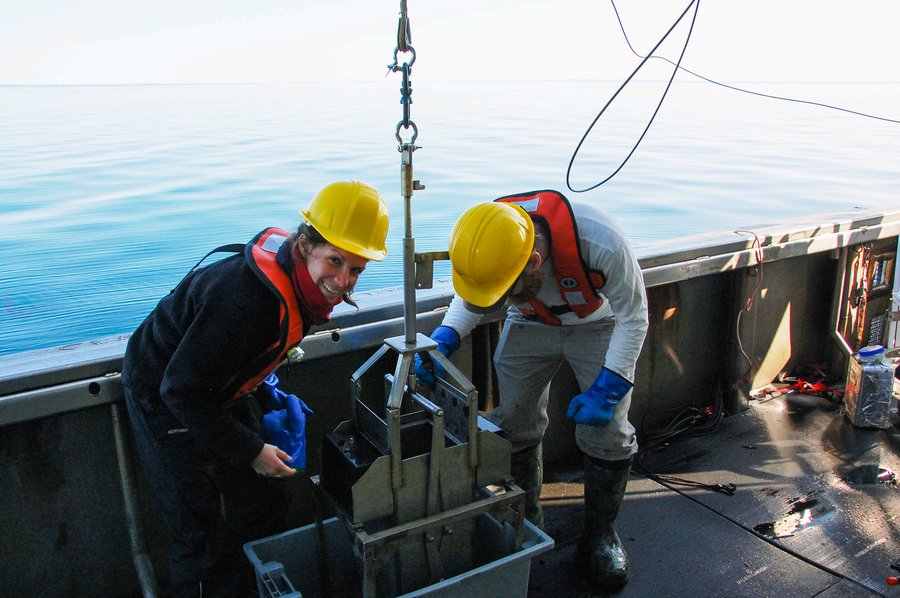

Audrey Limoges using a boxcore to collect sediment samples.