he world’s oceans are getting warmer and fish are moving habitats to keep up with changes. It’s as simple as that, right? Wrong.

When it comes to our warming oceans, and many other large-scale planetary changes, it is often difficult to predict the outcome. Cross-scale interactions, or processes that take place in one space or time and affect other processes in other places or periods of time, are often overlooked.

While many experts are working to consider what Blue Growth, or sustainable economic growth in the fishing sector, will look like, too often only a fraction of the picture is considered. This is particularly true in the unexploited Arctic Ocean.

For Stockholm Resilience Center researcher Susa Niiranen, the Blue Growth of Arctic fisheries is an interesting case.

"Unlike most other regions, global models project future increases in fisheries catch due to temperature-driven changes and northward movement of fish. These are state-of-the-art projections which have been referred to in different forums but they largely ignore social-ecological feedbacks, and economic and social properties are usually kept constant – if at all considered."

Susa Niiranen, lead author

Good for some, bad for others

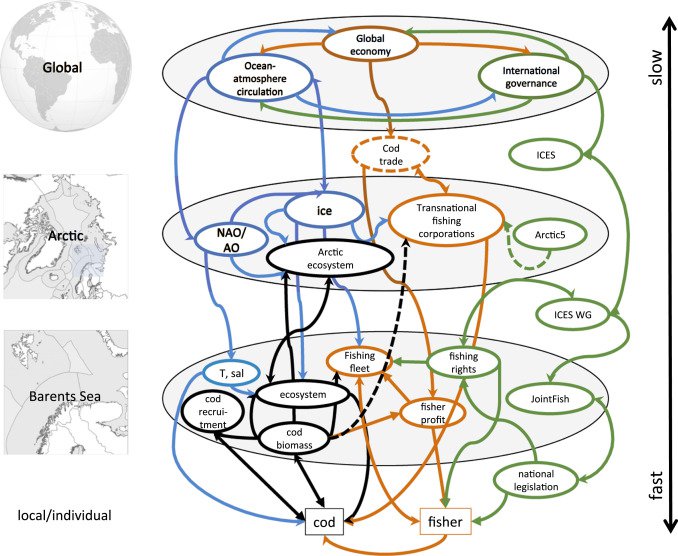

That is why Niiranen, along with centre researchers Thorsten Blenckner, Matilda Valman and others, all part of the research project GreenMAR, dive deeper into the question of Blue Growth in Arctic fisheries. More specifically, they look at cross-scale interactions at and across ecological, socioeconomic, and governance structure, and how these all come together to influence Blue Growth in Arctic fisheries. The authors also zoom in on two specific areas: the Barents Sea and the Central Arctic Ocean.

While it is true that some fish are moving towards the poles in search of more suitable habitats, it does not tell the whole story. Warmer temperatures can mean some fish species will experience increased population growth rates, whereas other species might experience negative consequences to their populations, such as predation as a result of lack of sea ice cover.

However, zooming out to the ecosystem level things gets even more complex. As species change habitats, interactions between species are also bound to change, including top predators and the Arctic Ocean ecosystem food web as a whole. Understanding how all of these smaller changes fit together, and what that means for the ecosystem as a whole, is a big challenge for predicting Blue Growth in the Arctic Ocean. Furthermore, understanding how these changes will affect the ecosystem and evolve over time, makes it even more difficult.

Summary of the types of cross-scale dynamics estimated speed of processes at each scale/level (the black arrow)using the Barents Sea as an example (NAO = North Atlantic Oscillation, AO = Arctic Oscillation, ICES = International Council for the Exploration of the Sea, WG = working group, T = temperature, sal = salinity).

Managing life below the Arctic sea ice

“Future changes in the Arctic are unlikely to affect all resource users in the same way,” Blenckner explains.

“Arctic fisheries should consider ecosystem changes and fish population dynamics, and concentrate fishing efforts on species that are sustainable to fish. The trade-off is that more specialized vessels can operate more efficiently, but are more vulnerable to ecosystem change.”

While a large highly mobile fishing company may be able to specialize in many species, small-scale fishers focused on few species would be at the will of Arctic ecosystem changes.

To help reduce small-scale fishers’ vulnerability to these ecosystem-wide changes, robust institutions are required. The authors call for “well-managed fisheries and strict government institutions” to help navigate fishers through changing time.

To manage a seascape in a cross-scale world, Valman highlights that, “Global commons cannot be adequately addressed at the national level due to the cross-boundary nature of climate, ocean ecosystems and economic transactions. Intergovernmental coordination and cooperation is required.”

The Barents Sea currently has strict fishing policies in place, and the authors highlight this as a strength for navigating the cross-scale interactions coming its way.

The Central Arctic Ocean, on the other hand, is currently unregulated, but Arctic nations (Canada, Norway, Sweden, Russia, USA), recently signed a declaration that follows the precautionary principle, requiring more research on the state of the fish populations before fishing is opened up. While this is a positive step, the declaration excludes several large fishing nations with their eyes on Arctic resources.

Where should we go from here?

The untapped resources of the Arctic Ocean mean there is a chance for sustainable Blue Growth to succeed. For this to occur, policymakers and resource users must be able to consider all of these interactions between species, climate, fishing practices, and unexpected events. An approach that allows for learning and adaptation to changes is necessary for navigating management of Arctic resources.

Vigorous, flexible and willing to learn

Adaptive management, a vigorous decision-making process that integrates learning and allows for flexible management, is thought to be key. As Niiranen concludes, “In this paper, adaptive management practices are called for to address scientific uncertainties and possible mismatches between governance systems and the scale at which the social-ecological processes take place.”

Being able to look at how the entire Arctic marine ecosystem works together, how our fishing practices and actions will influence the ecosystem, and what we can do for Blue Growth is a giant challenge ahead.

Niiranen concludes, “Such development is crucial for the future of the Arctic. If management of Arctic natural resources fails to address the right processes at the right scales, the Blue Growth potential of the Arctic can be easily lost.”

Methodology

In this study, the authors used previously published peer-reviewed papers to complete a literature review to help assess global impacts on Arctic fisheries. While they drew on literature that examined all parts of the Arctic Ocean, the authors focused on the Barents Sea and the Central Arctic Ocean as case study areas. They also choose to focus on different dimensions of these Arctic fisheries, namely ecological, socioeconomic, and governance structures.